Def Leppard Guitarist Solders Royal Metal Work

by Stephen Stern, executive editor

As bombs burst in Belfast nine miles away, an angry adolescent raged against the system. An atheist during the Catholic-Protestant separatist uprising, Vivian Campbell was trying to find his song. Armed with heavy-metal guitar defiance and lyrics of nonconformity that still hold true today, Campbell rebelled against school uniforms, classes, studies and a traditional or safe career path.

As bombs burst in Belfast nine miles away, an angry adolescent raged against the system. An atheist during the Catholic-Protestant separatist uprising, Vivian Campbell was trying to find his song. Armed with heavy-metal guitar defiance and lyrics of nonconformity that still hold true today, Campbell rebelled against school uniforms, classes, studies and a traditional or safe career path.

After numerous unsuccessful attempts to wake him up from his rock ‘n’ roll dreams, the Catholic school headmistress tossed the 16-year-old Campbell outside the schoolyard gate.

“She told me that the chances of making a career playing guitar were pretty slim.” He adds, “that was especially true in Belfast in the ’70s. But that’s all l wanted to do. I was very anti-social around that age. I would play all night, wake up at 6 a.m. to do some studies and then fall asleep in class by 2 p.m.”

The anger and the addiction started early in the town of Lisburn, located along the River Lagan in Northern Ireland. Vivian Campbell was one of four children born to Vivian Campbell Sr. who had a hide-and-skin business, and Mary Campbell, a former nurse.

By age 9, Campbell was bending his first strings and listening intensely to whatever guitar riffs, especially solos, emanated from the family radio. “Whenever the Beatles ‘Day tripper’ came on, I would turn it way up,” he says. “However, my mother hated the Beatles, she was more of a Simon & Garfunkel fan, but my father had the ‘Band on the Run’ (Paul McCartney) album.”

Radio and recorded music were key in a place where few outside musicians ventured because of difficult access and the perceived or actual dangerousness of Belfast in the ‘70s, explains Campbell. “As a consequence, I didn’t get to see many live acts growing up.” He did get to see Irish legends Thin Lizzy, and blues-rock multi-instrumentalist Rory Gallagher, at Belfast’s historic Ulster Hall.

Campbell infused a heavy dose of Thin Lizzy into his first professional band, Sweet Savage, and credits Gallagher for his blues-inspired style. “I was also influenced by Jeff Beck and Gary Moore, a thoroughly intense guitar player who never went through the motions.” Campbell says, “That very angry or intense style is what attracted me to heavy metal — it was my outlet from school. I would listen to someone like Al Di Meola for about six weeks. But with no bending strings, I’d lose interest. I like guitarists who torture their instrument. Plus, heavy metal glorified the guitar.”

But the glory days for metal bands and their blues-based guitar riffs, such as Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin, were on the decline with the advent of punk music. Coming to the rescue were Campbell and other members of Sweet Savage, which soldered together old metalwork with the quickened, punk-esque tempo and hard-edge sound. Sweet Savage is credited as one of the pioneers of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal.

Campbell captured this sound on 72987537 — the serial number he memorized from the Les Paul guitar — which took forever to afford, and seemingly longer for the wrong model to arrive from the USA Gibson factory. “I wanted a gold Les Paul Standard, put the deposit down, and went to the store weekly to check the status,” Campbell says.

“After six months, the store clerk tells me the good news that they have a Les Paul, but it’s the Deluxe model in wine red. I was fed up with waiting, and I thought that if the Deluxe model was good enough for Scott Gorham (Thin Lizzy guitarist), it was good enough for me. I put on some Humbuckers, sanded down the body to have that used and beat-up look like Rory Gallagher’s guitars, buffed it up and painted it black.”

Sweet Savage had a pretty good run, including touring around Ireland, opening for bands such as Thin Lizzy, Wishbone Ash and Motorhead, and influencing others, such as Metallica, which covered Sweet Savage’s song “Killing Time.”

“After knocking on every door and exhausting all the possibilities, I knew Sweet Savage was not going to make it,” Campbell says. “If it were going to happen, it would have happened, so I actively looked for a gig. I was very determined to play guitar for a living … so I called everyone.”

The phone burped back at 4 a.m., sometime in 1982, when a drunk Jimmy Bain found Vivian Campbell’s name in the phonebook. The only hitch was that it was Campbell Sr.’s number rung up by Rainbow’s rambling bass player. The elder Campbell quickly passed the phone to his son, who was invited to London to try out for a new band, Dio. The band was the namesake of legendary vocalist Ronnie James Dio, who was the front man for Ritchie Blackmore’s band Rainbow, and Black Sabbath, to replace Ozzy Osbourne. Despite the rude awakening, Campbell Sr. covered the travel costs, and Campbell and his 72987537 took off.

“It was very surreal to be in that situation,” he recalled. “There was Ronnie, Jimmy Bain and (drummer) Vinnie Appice in a rehearsal studio with rented equipment, jamming on Holy Diver. Ronnie’s got this tape rolling, and tells me to keep playing while he rolls a joint. It’s in the key of C, which is not the most guitar-friendly key. I play every guitar lick I know — my entire repertoire. Then I start playing it backward. He’s still rolling the joint. I run out of my own material and start playing double-stop Chuck Berry licks.”

With Campbell passing the test, Dio was complete, and with songs already in the hopper, an aggressive tour schedule quickly followed.

“Years later, Ronnie played the cassette tape back to me and said, ‘When you started to play Chuck Berry, I knew you were my guy.’ He also said that I showed up with just the right looking guitar — not some flashy guitar with the Floyd Rose (vibrato arm).” A few years later, neither the stop nor the Floydless guitar could prevent the inevitable

Campbell said his acrimonious departure in 1986 stemmed mostly from Ronnie’s unfulfilled promises of equity ownership in the band after the third album. It was the difference between being a salaried musician and dividing up a pool of performance revenues and royalties in the millions.

In addition to broken promises, Campbell was tired of conforming musically. “I had become an audiophile at that time, with a greater interest in being a musician rather than just a guitarist. I also took singing lessons but Ronnie didn’t want me to sing. He said, ‘You don’t see Ritchie Blackmore singing in Deep Purple.’ Ronnie was much older, like a stepfather, always butting heads. He was old-school metal, everything Dio did was very serious; lyrically, we were still slaying dragons. Van Halen and other metal bands had much more of a sense of humor.”

Almost comical by comparison, Campbell’s next major stop was on a video set for Whitesnake. He said, “We hadn’t played a single note together, but here we were making these rock videos. It was at a time when MTV was peaking, and we were an image-drawn band.”

With the exception of Adrian Vandenberg, who had played on one song on the new album entitled “1987,” none of the band members who performed on the album were in the videos. Campbell replaced John Sykes (formerly of Thin Lizzy), who was fired after writing and recording the album with Whitesnake founder and former Deep Purple front man David Coverdale.

“It was a closed shop, creatively,” Campbell said. “We were told not to submit any songs. We were not a band. It was a revolving door of musicians — perhaps, 60, before and after me. Coverdale was the only constant.”

Unable to conform to a band high on form and low on substance, Campbell left Whitesnake in less than a year, and produced Riverdogs’ first demo. He also played on Lou Gramm’s solo album, “Ready or Not.” He then replaced the guitarist from Riverdogs, which released an album to critical acclaim but had lackluster support from their record label. After that, Campbell rejoined Lou Gramm with his new band, Shadow King, which had limited success, and Gramm eventually returned to Foreigner.

“I was done with bands,” says Campbell. “I was tired of being hired and fired, and I wanted to focus on a solo record.”

Campbell’s solo quest was not only guided by deep introspection, but also the stark perception by others that he burned through bands as fast as his guitar riffs. However, once again, he was simply trying to find his own song.

Coincidentally, Joe Elliott, was trying to do the same for Def Leppard after guitarist Steve Clark had passed. The iconic front man and Campbell were old friends, having spent time in Dublin, where Elliott has lived since 1987. They had mutual friends, played soccer pick-up games, and a shared an affinity for the New Wave of British Heavy Metal.

“My reputation for going through so many bands preceded me, but Joe believed in me. In retrospect, I wish Sweet Savage had broken through the barrier. It would have been great to be in one band my entire career, but I am also grateful for my musical education.

“Joe had to convince the other guys that I was the right guy for the band. That’s why I think it took six months, literally, to join the band. We went to dinner together, the movies, played soccer and rehearsed. “

The courting was well worth it, says Campbell. “It was an exciting time. Heavy metal was still strong and grunge was yet to happen. Def Leppard’s last album, ‘Hysteria,’ sold 15 million records. And it was the embodiment of everything I enjoyed musically –playing guitar and singing with such great songsmiths. They took meticulous care with every song.”

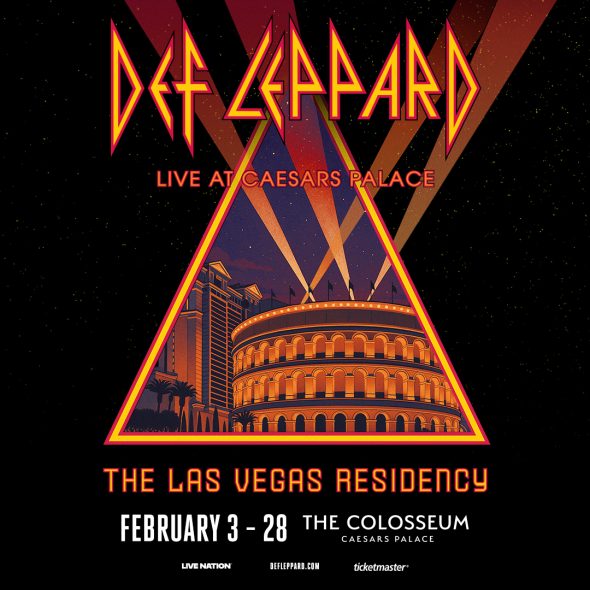

After warming up in a small Dublin club, Campbell took the stage with Def Leppard in front of 72,000 people at Wembley Stadium for the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert for Life on April 20, 1992. That first year, Campbell was a salaried player, but for the past 20 years, he has been a full-fledged partner in the band, which includes writing songs, including the first song release, “Work It Out,” on Def Leppard’s sixth album, “Slang” (1996). It was bittersweet for the guitarist cum musician, as it was the first Def Leppard album that did not achieve platinum success in the U.S. In fact, the album was a complete departure from the Def Leppard sound, notes Campbell, adding, “‘Slang’ was too much in left field; we compromised too much.” Even the iconic logo was missing its signature design, It was also during a time when various band members were going through some personal challenges.

It was an enigma wrapped around an enigma. “We (Def Leppard) couldn’t even get arrested if we tried at that time,” Campbell recalls. “Radio stations wouldn’t play us because the songs from the new album did not sound like Def Leppard. They also wouldn’t play the old songs because we represented the ’80s, and they didn’t want to have our songs played next to Soundgarden or Pearl Jam.”

He adds, “The record died on the vine, and it took a lot of wind out of our sails. The ’90s were a tough time for us, but we never broke up, we never gave up. Def Leppard have always been head and shoulders above other heavy metal bands, with a vast catalogue filled with genuine hits.”

The band’s next record, “Euphoria,” went gold in the U.S. It featured Campbell’s song, “To Be Alive,” from his solo band, Clock, and a return to their signature sound. Four more albums have been released since; “Mirrorball: Live and More” was the last in 2011. Considered one of the greatest bands in the history of rock ‘n’ roll, Def Leppard continues to fill venues worldwide. Campbell and other band members are writing songs for the next record.

Meanwhile, Campbell is planning to revive, temporarily, Dio for some tour dates next summer. Campbell is well aware that some Dio fans believe Ronnie James Dio would turn over in his grave on hearing the news of such a resurrection.

“We were all there at the start — the rehearsals, creating the sound, the records — and we have every right to play them,” he says. “Performing the songs is much better than complacency. The band will respect the music and perform them with the energy and passion they deserve” — just as Gary Moore would have expected from his Irish brethren. Campbell will be joined by Bain, Appice, Claude Schnell (keyboards), singer Andrew Freeman from Hurricane and Lynch Mob.

Returning to the scene of the crime is also a validation, of sorts, of where it all began. While other parents might have sent their long-haired, non-conforming school drop-outs packing, Campbell Sr. believed in his son’s rock ‘n’ roll dreams. He supported him and bought him the last-minute plane ticket to London for the Dio tryout, and then travelled to many gigs throughout Europe to watch him play. After the “Holy Diver” album went gold in the U.S., Campbell gave his father the framed gold album, which he hung proudly in his office.

Campbell has been trying to pay it forward ever since, for which Create Now recently honored him for his outstanding contributions. The Create Now organization “serves vulnerable kids ages 2-25 who have been abused, neglected, abandoned, orphaned, are left homeless, runaways, teen parents, substance abusers, victims of domestic violence, children of prisoners, gang members or incarcerated.”

An underdog in his own right, Campbell’s climb to rock royalty serves as an inspiration not only to kids in Create Now, but elsewhere, including in Belfast, where bombs still burst.

Their song remains the same.