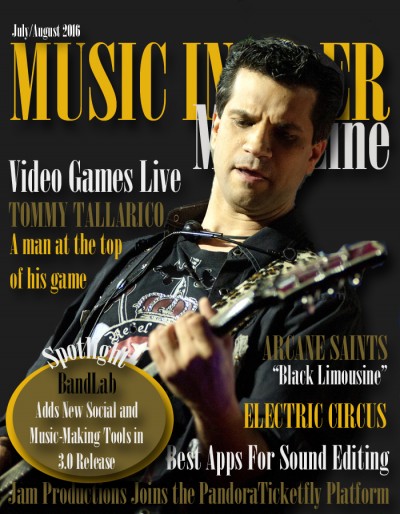

A man at the top of his game

Tommy Tallarico is nothing short of a phenomenon . Over the past 25 years he has carved out a very special niche in the music industry — one that he has built and grown over time. He has built a successful career composing and performing his original orchestral rock compositions as musical scores for some of the most successful video games in history. He is perhaps also best known as the creator of the immensely successful touring concert series, “Video Games Live.”

As a true pioneer of the video game music industry, he’s practically single handedly written the book about how to be a successful musician and composer in this huge, albeit not often considered career path as video game music composer. He has made it into the Guinness Book of World Records as the person who has worked on more video game titles than anyone else in history. That in itself is quite the amazing accomplishment. His list of credits is far too long to be listed here, but you can find a complete list on his website.

As a true pioneer of the video game music industry, he’s practically single handedly written the book about how to be a successful musician and composer in this huge, albeit not often considered career path as video game music composer. He has made it into the Guinness Book of World Records as the person who has worked on more video game titles than anyone else in history. That in itself is quite the amazing accomplishment. His list of credits is far too long to be listed here, but you can find a complete list on his website.

Brian McKinny: This first question I had for you was originally going to be the last question I was going to ask in this interview. However, after thinking about it further, I decided that it would be the perfect way to get this interview off to an impactful start, so here’s my first question: What advice would you give to any aspiring video game music composers who are seriously interested in breaking into the musical part of the gaming industry?

Tommy Tallarico: The answer to your question is actually quite simple. The game industry, unlike film and television is a lot easier to get into. It’s almost impossible to become a film or TV composer today, but in the game industry, it’s simple for a number of reasons. One reason is that everybody doesn’t hold their cards so close to their vests; they don’t view each other as competition. In game music, the simple answer is that it’s all about networking. Talent is about fifty percent of the equation, and the rest is networking. That part is what is most like working in film and television composing or scoring in Hollywood. However, it’s a lot easier to network in the game industry.

The quick answer is that you have to go to the Game Developers Conference. Their website is www.gdconf.com. That happens in March, every year in San Francisco. It’s a week-long event, and they even have a job fair with over two hundred booths, and they’re all game companies looking for artists, programmers, developers, and musicians — everything you can imagine that it takes to create a successful game. It’s unbelievable, and it’s a whole week full of workshops with the biggest names in the industry that come from all over the world, about twenty thousand people. If you’re serious about breaking into the industry that is the place to be, because it’s the one place where you can network the most successfully with the biggest names in video games the world over.

In keeping with the networking theme, there’s also the International Game Developers Association, the IDGA. They’re a non-profit organization, and their website is www.igda.org. They have chapters all over the world, and they all have monthly meetings, so again, the networking thing – you want to be going to these meetings and meeting people in your area who are doing the things you want to do in games. And the great thing about the industry right now and why it’s so easy to get into is because of the explosion of mobile gaming. There are literally thousands of games and programs being released every week! We’re talking about tens of thousands of smaller developers. You know, you can have a couple of college kids in a dorm room making money by creating video games.

It harkens back to when I first got involved in the industry in the late eighties, early nineties when back then, teams were small. You had a programmer, an artist, a sound guy, and maybe a designer. So you had teams of three, four or five member teams and that was it, and we were making games for Super Nintendo, or Sega Genesis, or whatever the new platform was at the time. Now, things have kind of come full circle. Here it is almost thirty years later, and you’re seeing the same kind of resurgence in that form – the small game development team. Granted, there are still teams out there, of course, like World of Warcraft with Blizzard Entertainment having hundreds and thousands of people who are working on these games. So the big game development teams still exist out there, but now the majority is made up of the smaller teams, so now the smaller teams have become much easier to access to get to all of these folks.

Now, once you’ve got your foot in the door after meeting these people, how do you go about getting directly involved? Offer your services for free at first. Say, “Hey, let me do one song for your game. I’ll do the first one for free, and if you like it, you can hire me to do more.” Don’t be afraid to ask people what they need, because the reality is that every game developer out there, like most everybody else in any industry you can think of, especially the entertainment industry, is just too busy. Everybody has too much stuff on their plate, right? So just by getting in there and making friends with people, ask them, “Hey, is there anything I can do to help?” or “Can I intern at your place for a couple of weeks for free? Just let me show you my worth – I’ll take out the garbage, I’ll bring your coffee, or sweep the place out!” Whatever it takes to get the foot in the door and show people your worth, and that you’re serious.

And now that you’ve gotten in through the door and proven your worth, then you can start talking about getting paid and playing a bigger role, depending upon your skill set and experience level. I’m not advocating for people to work for free for any great length of time or to become someone’s slave, because there’s a whole other dialogue about that. But I am advocating doing something for free in order to get a foot in the door. It’s funny, because there are two sides to this argument, and each side hates the other. “You should never do any work for free!” I don’t agree with that, either, because I can tell you my story about how I got into the industry, and why that strategy works and has worked for so many people who are successful in the industry today.

There’s an amazing website called gamasutra.com that’s run by the people who put on the game developer’s conference. It’s a website that’s been around for fifteen or twenty years, and they have tons of great information about the gaming industry, from articles to advice, as well as industry job postings, and it’s all broken down by subject – audio, arts, programming, music, producing – every aspect of the industry is well represented. And, since you learn so much – it’s free, just go on there and start reading – they literally list every single game publisher and developer in the world. You can even search for people in your geographical area so you can find the people who live close by who are working in the industry for you to network with. It’s an absolutely indispensable resource.

The final thing I’d tell folks who are interested in the game industry in general, is to go on Amazon.com and search for the topic that interests you, whether it’s game audio, development, art design, producing… Whatever it is, someone’s written numerous books about it so jump in and pick a topic and start reading the stuff that’s being written by the people who are in the industry. It’s the cheapest way I know to learn about the industry in depth. But if you’re specifically interested in the music side of the industry, there’s a whole website just for that, called the Game Audio Network Guild, or GANG. It’s a non-profit organization that’s dedicated to the game music industry, and in the interest of full disclosure, I was the guy who created it, and I’m on the board of directors. It’s an incredible resource that anyone who wants to find out more about music in gaming should definitely check out.

McKinny: What about the musician who isn’t schooled in music or orchestral writing?

Tallarico: The reality is that any musician is going to be like, “Hey, I never thought of that! I could write music for video games!” And the great thing about that makes it different from film and TV it is that when you think of film or TV music, you think about big, orchestral things — and they have that as well with games like Halo, Warcraft, with these big film-like stories. But again, if you’re talking about apps and stuff, especially mobile platforms today… Look, if you only play the accordion, there’s probably an app out there that an accordion would be exactly what they’re looking for! Or if you only play slide guitar, there’s probably a great fishing game out there that would be awesome for some bluesy slide work to accompany it. Whatever it is, there’s probably some game or app out there that your music would be perfect for you and needs your stuff. The film and TV industry can’t say the same; it’s all pretty formulaic and mostly orchestral, but games are rock and roll, electronic music, orchestral, or a combination of all those things and more.

As a musician, you’ve got to be looking towards games, because it’s the easiest music-related performance and compositional industry to get into. And by the way, it pays great for entry level people! Once again, in the film industry, it’s quite the opposite. In the film industry, you’re doing work for free, just trying to cover your expenses, and you’re working your ass off for six months or more at a time just to get a credit. And then maybe after doing that for ten years, you’ll finally get to do the score for a B-rated film. Maybe, if you’re lucky, you’ll be one of those ten or so people like a Hans Zimmer, or a John Williams who makes a million dollars a year (or more) if you work for ten years or more for free. In the gaming industry, the average person is making $60k to $100k a year, so our income average is a lot higher, but the highest paid guys in the industry are only making a couple hundred thousand a project or so, as opposed to a million or more in film — if you’re one of the lucky few.

It’s a bit of a trade-off, but most people find that the odds of sustaining a steady income and flow of opportunities in the game industry are a much better bet in both the near and long term, and the work, the outlet for musical creativity is just as rewarding. We’d rather have the higher average for everyone.

McKinny: Where did you grow up, and where did you go to school, and how did you get involved with the conjoining of music and video games?

Tallarico: I never went to school for music, I’m completely self-taught. I grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts on the east coast, and I was always involved – my two greatest loves were always video games and music. My cousin is Steven Tyler of Aerosmith. His real name is Steven Tallarico, so I grew up going backstage to Aerosmith shows, and I always tell Steven – in fact, I’m seeing him later today, he’s playing in LA tonight – but I always tell him that the greatest gift he ever gave to me was, when I was growing up – eight, nine, ten years old — when you see this person who’s your cousin, you see him at summer barbecues and not as someone or something else, and then to see him on stage with Aerosmith, performing in front of twenty-five thousand people… It just seemed normal, you know? It wasn’t the impossible dream to me. To me, I always thought, “Wow, what a great time he’s having on stage, and what a cool job this is! That’s what I want to do when I grow up.” So it never seemed like it was something that was too difficult or impossible to achieve. You give a lot of people that idea, and in their head they say, “Oh, I could never do that.” To me it was like, “Well, he’s doing it, so why can’t I?”

So, while I was growing up in Springfield, the two greatest loves of mine were video games and music. So much so, that in the late 70s, when I was 10-11 years old – maybe your family was like mine, where we had the rip-off Pong machine – mine was the Coleco Telstar, where you hook it up to the back of your TV, put it on channel 3 and you’re done. And of course in the seventies there was the arcade explosion – Space Invaders, Pac Man, and Missile Command – all the stuff that was coming out in the late seventies, and then there was Atari…

During that time, I used to take my dad’s big-ass cassette recorder – it was huge – and I’d take that down to the local arcade, which was actually part of a pizza shop, called “Papa Gino’s.” And we also had a huge arcade at the mall down the street, and that’s where all the new arcade video games would come out, and the place was called “The Dream Machine.” “Here’s the latest game, kids! It’s called Donkey Kong!” And we’d all line up with pockets full of quarters, ready to play!

So I’d take my dad’s cassette recorder down to the arcade and I’d record all my favorite game sounds and game music, and then I’d do the same thing at home with my Atari or my IntelliVision. I mean, it was just a lot of bleeps and bloops; there wasn’t a lot of music back then in video games… But I’d take that tape, and I’d splice it together to keep the original quality rather than making copies of copies, and then I’d grab a guitar, I’d invite all my neighborhood friends over, and I’d charge them a nickel and I’d jump up in front of my television set with the video games playing behind me on the screen, hit play on the tape and I’d jump up and start playing guitar along with it and put on a video game show. That was the first iteration of Video Games Live. The whole show manifested out of the mind of a ten year old. Still today, I mean just last week we played to 60 thousand people at two shows at the Birds Nest (Beijing National Stadium) in Beijing, China, their national Olympic stadium, the largest stadium in Asia. We did two shows there, and it was me running around on stage playing music with video games on the big screens behind me and the Beijing Symphony, and I was telling my conductor, “This is just like when I was ten years old, running around my house, and now I’m just doing the same thing on a bigger scale at the Birds Nest, so it’s kind of crazy how life works out.

McKinny: The shows you just did at the Birds Nest in Beijing; were those shows part of a game convention, or is that part of a tour?

Tallarico: We’ll do two or three of those a year, we’ll play in association with a gaming convention. For example, the biggest video games convention in the world is called GamesCom, and it’s every August in Cologne, Germany. They get somewhere around five hundred thousand people all over Europe and the US attending that convention. The biggest one in the US is called E3, and they draw about one hundred thousand people. The second biggest game convention in the world is in Japan, and it’s called Tokyo Game Show (TGS), and has roughly around three hundred thousand in attendance, but GamesCom is the biggest one by far. For that one, we’re doing two shows right in the game convention on the Blizzard Entertainment Stage, because we’re going to be performing Blizzard games, and introducing brand new world premiers of both games and music that no one has ever heard before, so that’s pretty fun. So we do about two or three conventions a year. But the thing in Beijing, that was just a show, and in fact, we’re going back to China for thirty-six days in September, where we’re playing sixteen shows in fifteen different cities, including Beijing again where we’ll do two more shows there. And that shows how crazy the gamers there are in China!

McKinny: What kind of issues have you encountered with intellectual property and licensing your music in overseas markets, such as Asia and South America, and has the large black markets in those regions caused you to do business differently there?

Tallarico: Yeah, I would say to get as much money up front as you can. I mean, there’s two things here: there’s my show, Video Games Live, and with me getting the music from the publishers to use in the show – the images, video, and all that, and then there’s me as a musician licensing my music to the publishers, so I play both sides of the game. I have to ask permission, and then I have to give permission. I’ll tell you both sides so you can figure out which one you’d want to use, or maybe use both.

As a composer, most of the work that we do is a work for hire, and it’s a buy-out, for the most part when you work on the bigger games. This works more like the film industry, because, by the way, Danny Elfman, John Williams and Hans Zimmer – none of them own their own music, either. They’re work for hire. Now, just because it’s a work for hire, doesn’t mean you have to give up all of your financial rights at all. The only reason a work for hire is a work for hire is because that company has created something that they own the intellectual property to, and they need to be able to control it. They don’t want to have to come to you and ask if they can use the music they hired you to create for their movie trailer, or whatever. Also, they don’t want the music that you wrote for their film to end up in a beer commercial without their consent, and then they get pissed. So I get it. It totally makes sense why they need to own it and control its use.

The control is the thing they most desire, especially when they do all these deals globally. Say they do some sub-licensing deal with a DVD manufacturer in Bucharest, and they can’t pay the same amount as they’d pay you if you were doing something in the US. They need to control it; they need to be the one to make the decision, not you. They can’t be held hostage to your demands. But just because they control it doesn’t mean you don’t get paid! So when I do my contracts with game companies, I put specifics in my agreements – and this is all on Audiogang’s website that I mentioned before – we even have example contracts that people can download, we’ve made that available to the world. I’ll put things in my contracts like every time the music is used on a different game platform, I want to get paid.

For example, if you’re doing music for a game on Playstation 4, let’s say they use the same exact music on Xbox, then they use it on Nintendo, they use it on PC, Droids, or iOS platforms, and then five years from now some new stuff comes out and they release it on that new platform we haven’t even heard of yet, I get paid. I can put that in my contract, and I can come up with whatever dollar amount I want, whether it’s $5000 dollars, $10,000 dollars, or whatever. I’ve gotten paid as high as $50,000 dollars per platform. And there is stuff that I worked on twenty five years ago and I have it in my contract where, oh look, it’s super popular again and now it’s on the Android platform! Boom! I get paid. I mean, who knew 25 years ago that people would be playing games on their cell phones? Nobody! But, who knows what’s going to come around the bend twenty years from now? As long as you have one line in your contract stating that every time the music gets ported to a new/different platform , I get “X” amount of dollars. So you’re covered for the rest of your life, right? So that’s a smart way to do it.

The other way is to be paid on bonuses. For example, a cumulative total of all of the sales of the product – you can go “per platform” or better yet, put all of the platforms together. So you say to the publishers, “What’s your breakeven point?” They might say, and make no mistake; every company knows what their breakeven point it. They may not want to tell you, but they know the number, and all you have to do is be a little bold and ask. They may say, “Well, it’s a hundred and fifty thousand units.” Okay, great. So if your breakeven point is 150 units, at 250k units, you give me a bonus of ten grand. They’re making tens of millions of dollars at that point, so “hey, kick me down ten grand!” That’s fair, isn’t it?

And then there’s music publishing as well. The other thing I say is, “Look, if this music makes any money outside of the video game industry, or the video game – the specific thing you’re hiring me to do – we split that money 50/50. So that’s generating income for you. If they do a TV commercial for the game, and the music plays in the TV commercial, that’s a public performance on television. And if it’s on a major network and it’s played in rotation fifty times a day in a high market, that’s going to generate money from ASCAP and BMI, for both you and the publisher as well. So the publisher is getting a sort of rebate back from the ad on the money spent to create the music. It’s a win/win, and you’re splitting it 50/50, and that’s fair, isn’t it? How can anyone argue against that sort of arrangement being equitable? And if a company were to argue against it, well then that’s a company I wouldn’t want to work with, anyway.

Those are the things I laid out for the big companies. Now, if I’m talking to students, and I’m talking to people looking to get into the industry, or just lower lever game developers, then I structure it a little differently, because you can’t just walk away from the project. You can’t say “Hey, this isn’t what I want or else.” They’ll be like, “See you later. We’ve got fifty other guys waiting in line behind you.” So what you want to do in that instance is say to these smaller companies, the ones that are doing mobile apps or whatever, “Look, you can’t afford to pay me $100k for the music,” and none of these apps can – they might have a five thousand dollar recording budget or something like that – say, “Okay, I’ll take your five grand, but I want to own all the music – it all belongs to me, so I’m going to license you the music for five thousand dollars, and because I’m going to spend a lot of time, and I may not get my money back at all, I want to take part in the royalties from day one.

So, because I’m going to take the risk and work my ass off, just like everyone else on your team, the difference is that I’m not getting paid a salary. So that puts me in the royalty pool, and maybe that’s just ten cents a unit, or whatever. But that’s an arrangement that’s very fair and negotiable, and can be very lucrative as well with a successful, popular app or mobile game.

If these companies want me to pour out my soul as a musician, as an artist for their game product, then they don’t get that for free. People need to understand that music has value, especially in movies and most especially in video games, where one third of the total experience is the music. So again, that’s my negotiation tactic when I talk to these folks. I say, “So, how much are you spending on developing this game? Oh, ten million dollars? That’s cool. Hey, I’m excited to be a part of it. So, let me ask you this: of those ten million dollars you’re spending on this game, why is there only fifty thousand budgeted for music, when it’s a third of the overall experience?” Now, I’m not asking for a third of the budget, three and a half million bucks, but half a percent of the budget is stupid. By the way, the film industry does the same thing… “So I’m not asking for a third of the budget, but I will ask if we can get one hundred grand from a budget so large. Could we get one percent instead of point five?” It’s all how you talk to these folks, and making friends with them.

McKinny: Do you conduct your own contract negotiations, or do you have an agent do that stuff for you now?

Tallarico: I don’t have an agent for my composing career or contract negotiations. I do for my touring career, but those are two different animals, touring and composing. I tell people all the time, when they’re looking to get into the video game industry in general, but especially for music – people put too much time into honing their talent and their craft — and that’s a horrible thing to say, especially to a musician’s magazine, my god! I mean, I can hear people saying, “What the hell is this moron talking about? Is he telling me not to practice as much?” Yes, I am. To really be successful – if you’re a piano player, and you’re practicing ten hours a day, and you are honing your craft to become the greatest piano player on the planet, that’s fantastic, that’s great. I applaud you for your talents. But, the guy who’s practicing five hours a day, and the other five hours are spent on himself to better his business acumen, to better his networking, making calls, or reading a book on how to win friends and influence people – there’s a million of them out there to help educate yourself about business. All that knowledge is just as important as knowing your C scale back and forth, so I think that it’s important for people in the 21st century to realize and understand that.

Another thing is, with YouTube and all the other digital outlets around the Internet, you don’t need a big record label these days to get recognized. You don’t need TV anymore. One of my friends, Lindsey Stirling, is a violinist who became famous through YouTube. She’s played with Video Games Live before, and now she’s so big that I can’t even afford her on my own show. But she’s amazing because she’s built this incredible crowd and this incredible multi-million dollar career through YouTube!

So again, spending those five hours a day creating a video and putting it on YouTube, and how you’re going to market that video – spend a little money on Facebook to market that video, and it all starts to go from there. But just sitting there in your room practicing your instrument for ten hours – again, kudos to you – but take half the time and spend it on yourself; marketing yourself, improving yourself in regards to getting to understand what your positive things are, what your weaknesses are, and then improving on those weaknesses, whatever they may be. Maybe you’re terrified of public speaking/talking to people – guess what… You’re not going to get a lot of gigs. You have to become friends with the people who are going to hire you, and if you’re not good at doing that, take a course, read a book, go online and watch some videos that will instruct you on those things – there’s just so many resources out there to take advantage of, and most of them are free for the asking/taking.

That’s the thing that the musicians I talk with fall down on. A lot of guys/gals just want to be on their own, and don’t want to deal with all it takes to be successful from a business standpoint, and that’s great if that’s all you want, but you can’t be successful financially if you take that approach. Your chances will improve exponentially though, if you’re actually out there making connections, networking with the people in the industry you need to meet in order to get work and get paid. It’s a great industry, with millions of opportunities for anyone who wants to try their hand in the game music industry.

Tommy Tallarico website

Tommy Tallarico on Facebook

Video Games Live clip at Beijing China’s Birds Nest National Olympic Stadium

Video Games Live on Facebook

Game Audio Network Guild website

International Game Developers Association website

GamaSutra website