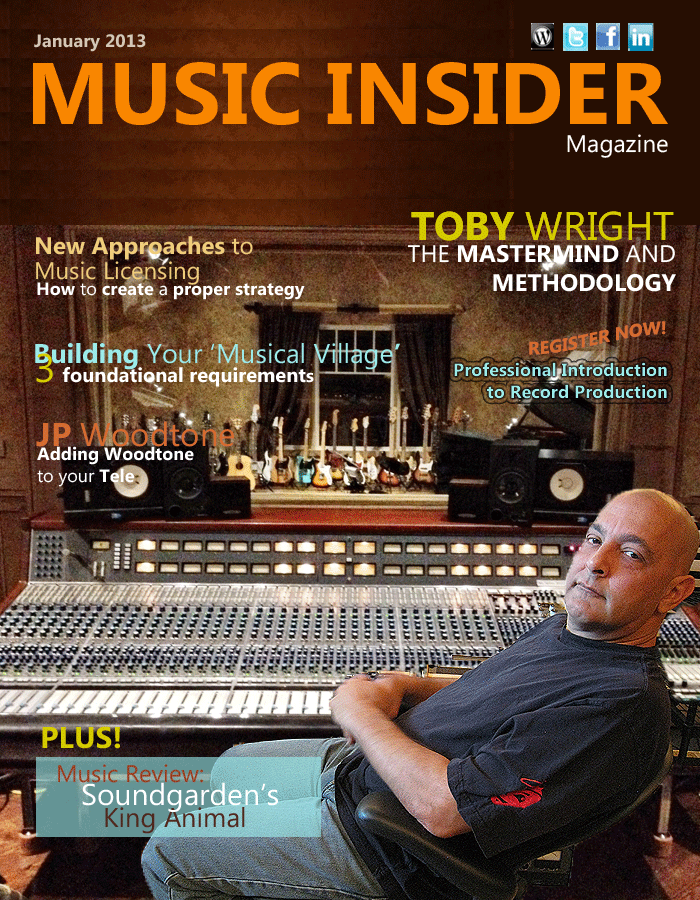

The mastermind and methodology

by Brian McKinny, editor, Music Insider Magazine

In speaking with Grammy Award-winning, multi-platinum record producing, innovative recording engineer Toby Wright, time has a way of disappearing. Recently, I had the opportunity to sit down and talk with Wright about his career, how he does what he does, and what shaping the careers of many artists and bands means to him.

Suffice it to say: Get Toby Wright started, and you might as well get comfortable. The man has a lot to talk about. And I didn’t want to miss a single word … Wright has worked with so many artists and bands that I know and love, he’s really been an integral part of my musical life, well before I ever met or knew anything about him.

His reputation for taking artists and bands that are notoriously difficult to work with and getting them into the studio to create their magnum opuses is simply legendary. From his masterful work with Alice in Chains on the album, “Jar of Flies,” to the incredible breakout album for The Wallflowers, “Bringing Down the Horse,” and countless others, Toby Wright has built a business out of “not fucking around.”

He has that rare ability and focus to bring out the absolute best in a band or artist in the recording studio, allowing that brilliance to be distributed to the masses.

Want to learn a thing or two — like what it takes to make great music? Well, sit down and take the load off, because school is about to start.

MIM: Tell me a little about yourself. What was your upbringing like?

Toby Wright: My dad was a professional saxophone player, so music has been in my family forever. He actually ran Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts for a while, so that provided inroads to amazing artists in the industry.

MIM: What brought you to production and recording engineering?

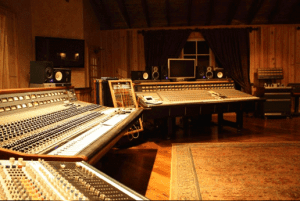

Wright: When I was learning to play the clarinet, flute, saxophone, piano, guitar and all that kind of stuff, I didn’t feel like I was really that great of a musician, even though I had played a bunch of shows, passed all these talent auditions, and so on … I had all these great reviews, but I didn’t really feel it. I found I had much more interest in being behind the scenes, creating the entire package than I did playing just one instrument in an orchestra, or being the guitarist in a band, or something like that. So that’s what I went to school for in New York at NYU, and I subsequently got a job at Electric Lady Studio in New York.

MIM: What were some of the most important lessons you learned while working as a studio maintenance technician, and how did you apply those lessons to your first assignment or project as the lead recording engineer?

Wright: Knowing your gear, and knowing how to operate it to its full potential. And then there was studio etiquette, for sure — how to act in the studio. Knowing what NOT to do is sometimes more important than knowing what to do, because you can be thrown out of a session in a heartbeat. My sessions today are still very focused on getting it done, especially because today’s budgets are so damn small. You have to maximize every minute in the studio. If the singer’s late, sometimes we’ll impose penalties and fines. It just depends on the band, and their financial status, and so on. I guess a great work ethic is one of my attributes that I stand behind, that I bring forth to the table, and I try to instill that ethic in the musicians who I work with.

MIM: What was your first big recording project? Who was the artist/band and what was your experience working on the album?

Wright: Back in the mid-eighties, I built a studio in North Hollywood, California called One on One Recording. That studio was amazingly successful all of a sudden. Big, huge rooms were en vogue because of the big drum sound that they gave, and so we built a 50 by 65-foot room with 30-foot ceilings, and something like the first 13 or 14 artists who came through there ended up going triple-platinum or better. I don’t think that was necessarily because of the studio, I think it was just the times, with all the popular hair bands. I had looked through the Billboard top music charts, and I had called the top 30 producers or their management company, and told them that there was a brand new studio opening up, come and check it out. I happened to be the only person there, so I ended up getting to work on every single one of those projects, in one capacity or another.

My first stepping outside of all that was with Alice in Chains.

I did two songs with Alice in Chains that were successful before that (“Jar of Flies” album), “A Little Bitter,” and “What the Hell Have I,” which are on the soundtrack for Arnold Schwarzenegger’s film, “The Last Action Hero.” Another prominent mixer was hired to mix them, and the band hated how they’d come out, and so they hired me to do “Jar of Flies.” And so, “Boom”… Jerry (Cantrell, guitarist/vocalist for Alice in Chains) called me from Australia and said, “Hey, how would you like to do an EP with us?” and I said, “Absolutely!” And so we went in, they had booked 10 days in the studio, and when they got there, I said, “So, let’s check out some of those songs you want to record.”

“Funny thing about those songs,” Jerry said, “What’s that?” I asked. “Uh, we don’t have them.” I’m like, “Really?! So what’re we gonna do for the next 10 days?” Jerry said, “Well, do you mind if we just jam?” I said, “No …”

Jam with the best band in the world?! Let’s start fucking rocking right now! And so we did. We jammed for those 10 days, and the whole “Jar of Flies,” was written, arranged, recorded, and produced in those 10 days.

When I asked to hear what they had written, at one point Jerry said, “Well, I think I have one thing,” and he started playing the chorus for “No Excuses.” That chorus seemed to come to him so easily; I think he just made it up on the spot.

MIM: Hypothetically, would you prefer to deal with a band with talented musicians who write crappy songs or a bunch of average musicians who write good songs? Also, how would you approach each scenario differently to achieve a good result for both?

Wright: I think I’d probably rather deal with the good songs, because from my experience, every indicator is that good songs sell music. Crappy songs don’t sell music. Those are the people who give their music away online. That’s the wrong approach. I think Sharon Osborne is the perfect example of that. She tried to make Ozzfest free one year, and nobody came. She put on another Ozzfest the next year and charged regular ticket prices and she sold out. The lesson from that is people value things that they pay for; they do not value things that are free, period.

I don’t do “back-end” deals anymore, because there’s no such thing, especially with bands that aren’t signed to major labels, and there’s a million of those out there right now. Even if they are extremely talented, what’s my incentive? I often ask, “Can I see your marketing plan, please?”

That question usually makes them freak out. They’re like, “Oh, uh… We’re in the middle of writing that now…” Well, when you get your business plan written, let me know I say. And then I’ll never get a call back from them — ever. They’re scared and usually broke.

But if you have your ducks in a row and you’re really going to get out there and sell your music and make a profit, and you’re serious, then you have to know that this is a business. It’s not fucking around. I don’t fuck around. I make music for a living, and I would love to help everyone out, but at the end of the day, I must pay my bills, buy food, and put gas in my car, the same as everybody else. It’s just life.

MIM: Over the years as a recording engineer and producer, numerous changes inside and outside the industry have affected popular music and the music industry in general. As you see things now, what have been some of the biggest changes — for better or worse — that you have seen, and how have those changes affected how you engineer or produce music today?

Wright: The personal computer came along and revolutionized the music industry. Apple came along and took over, and now they own it. Before, it was all about the record companies, and the record companies selecting what to put out, what people heard, and they did the screening process for the public.

Today, you don’t have that. You have “one-button gratification” — I can go on Spotify, type in the name of any artist and their whole catalog pops up. And I can search the Internet for unknown artists who aren’t on Spotify as well. I have a one-button touch to the globe; whereas before, if I was a musician, I would have to go through a label, and go through very limited distribution, pray that they (the record label) liked me and would push my record.

Now, it’s much more of a self-serve industry where musicians have a chance to do it for themselves. And if they fail, it’s all on their own. It still takes literally thousands of people to make a hit record. I don’t see the radio industry changing very much. It’s always going to be “pay to play.” But there are many different ways around that.

One of those is to break out in Europe. The reason being, Europeans inherently like music and entertainment better, and they’re more open to different kinds of talent and entertainment than Americans. In my travels, I’ve found that Europeans are much more open to everything, from fashion and design to sex and everything in between. Take some little girl who’s dressed like some little punk/Goth chick, and she’s listening to Barry Manilow and loving it! I mean what the fuck? Next minute, she’s listening to Slayer, and she loves both for what they are. You wouldn’t catch that happening here. People are way too self-conscious. They think I’ve got a piercing in my nose, so I can’t listen to Barry Manilow!

One of the other changes in the industry is the degradation of audio into MP3. Before, we had vinyl. Vinyl was awesome. We all took it for granted, and then someone said, “Oh look! This thing can make it better! It’s smaller, it’s shinier, and it’s called a CD.” And that was cool when it first came out, because you’ve got a lot of early CDs that were made from vinyl, so they still had that warmth. But when we moved into the all-digital age, audio became very sterile, and it really hurts my ears. When it’s all digital, I have a problem with how it sounds. I can hear all those rogue frequencies, and it’s not good. At first, I didn’t know what it was, and then I went back to listening to my record collection, and I went, “Oh, I know what it is! It’s all-digital, and I prefer the warmth and natural sound of analog.”

MIM: What are some of the ways you’ve found to get around the sterile sound of digital recordings, and maintain the warmth of the old analog recordings when you’re tracking new music?

Wright: Use it. I mean, I’ll still track bass and drums (in analog), depending on budget, and sometimes guitars; usually, it’s just bass and drums that get tracked in analog. Since digital is so good at preserving (already recorded in analog) sound, I don’t go to 88.2, I don’t go to 96, I don’t do any of that nonsense because there’s inherent things in the code that amps up the top end on 88.2 and 96, and it’s just super unnatural to me. The most natural sounding format to me is 48k, 24-bit. I’ve gone back and forth, back and forth, beating myself up over it.

When ProTools first came out, it was 16-bit software, and their reps came to the studio and said, “Hey, you wanna try this out?” I said, “Sure, I’d love to try it out, but if it doesn’t live up to what I already know, it’s outta here.”

I tried the original 16-bit stuff, and I could tell instantly, so I told them that I could hear the difference and to get it out of here. They got really mad at me for a while and then they said, “Well, maybe you’d like this 24-bit stuff?” So they brought in their Beta 24-bit stuff, and I was like, “Whoa, there’s something wrong with me. I can’t tell the difference!” So I said, “This is interesting, let’s give it a try …”

Then I tried 44.1 24-bit, and I could tell the difference, but it was really close. And so when they brought me the 48k 24-bit stuff, I said, “Whoa, I can’t tell the difference between analog tape and this. Let’s keep this.” But then they got the bright idea, “Oh, we can do 88.1 and 96k… Higher sampling rates are not necessarily better. When it comes to audio, a lot of manufacturers, and I think the public, especially, have missed the boat. They’re into ease and convenience, so they listen to MP3s. I just can’t. It actually hurts my ears.

MIM: How do you guide a band through the recording process to help them define their overall sound, especially when they don’t know what they want? Do you take each song as they come, or do you approach the project as a whole?

Wright: The best way to answer that question is that I take the entirety of what that band has created, whether it is past albums and new stuff, or just a pile of new stuff … Say you give me 25 songs, or 25 proposed songs, and we’re going to pick a record; we’ll pick 10 songs, maybe 12 and record 14. My first 10 will be the best package that represents that band. And then I’ll add four more songs that are kind of outside of what those first 10 represent. They could be singles, or what have you, but they’re outside of the first 10.

Bands that sit down and write 30, 40, 50 songs usually have some common thread between them already. It’s not like I have to go in and say, “We’re gonna build you in this way.” I don’t believe in any of that stuff. I believe that when you run across an artist that has 30, 40, 50 songs, there is a commonality in there somewhere. You have to find it, and bring it out — whatever the public needs to put it in their tiny little category and say, you’re an alt-rock band or a country band or whatever you want to term it.

I don’t “genre-lize” music at all. You call it jazz, rock, or country, I call it music. So it’s a matter of finding what that commonality is in the songwriting, and exploiting that. And then whoever decides what genre to put them in, or whatever radio station to try to play them on, takes his or her best shot. And then all of a sudden, the band shows up on some genre-lized chart. And that’s fine.

But to answer your question, I just try to bring out the best in the artist, whether it’s a rock band or a classical orchestra. Whatever it is, I’m there to exploit everything great about them; try to hide what may be not so great, and to bring out the best songs that I can.

I’ll sit down with a vocalist or the lyricist, and go over the songs, word by word; to make sure the grammar is close to correct. There’s a lot of stuff that you can’t have correct grammar on. It just doesn’t sound right. For instance to use the words “want to” instead of “wanna.” It can make things sound very square.

First, it depends on the rhythm, and whatever sounds the best. And second, what’s grammatically correct. If it is correct, cool. If it can’t be correct because of whatever reason, that’s cool, too; as long as your audience can make sense of what you’re saying. It has to make sense to everyone out there, not just you as the writer.

MIM: With an eye towards the future, where do you see music production and engineering going in the next 10 years? Do you see more control over creation, production and distribution going to the artists as the trend is now, or do you see other opportunities for record companies to take back some of the control they’ve ceded to the artists, especially with all the online direct marketing through the Internet with outlets such as iTunes, Amazon.com, and Rhapsody media sellers? Will the record companies still be necessary to the industry 10 years from now?

Wright: That’s a really good question. Right now, I see it as the artists leading the way in the creative world. Artists in general are not business people, so the two will coexist together for a really long time. When you find an artist that’s both, that’s a dream come true.

Jack White, for instance, he’s truly an independent artist who’s got his shit together to the point where he’s started a record company, and it’s making a splash and making some money. The company goes out and finds real musicians.

If you go on their website, and you look at some of their videos, you go, “Who the fuck is this?” And then you look at it deeper, and you say, “Holy shit, look at that guy!” They’ve got this 63-year-old guitar player who’s kind of a “country-esque” blues player, Seasick Steve. He blew me away.

Jack is going out there and finding great musicians. He’s putting them out there, and people are digging them because they write great music. Which brings us back to point one, great songs, and great music will sell, period. So, he’s subscribing to that, which is great. Meanwhile, you have these single-minded people at the record companies going, “Nobody will buy that because he’s too old.” Really?

How about Susan Boyle? Let’s examine Susan Boyle for a minute. Here comes this no-prom-queen looking housewife, and everyone booed her before ever hearing her. And then she opened her mouth, and this wonderful sound came out, and there wasn’t a dry eye in the audience. Case in point — listen before you form an opinion. My hat’s off to Simon Cowell for bringing that point across to the music industry in America. It’s a great thing when someone can prove it to you within five seconds. He set an example with Susan Boyle; she’s a middle-aged frumpy woman, and they were looking for all these teenyboppers to lead the way — ain’t gonna happen. I know very few 18-year olds who can really sing.

There are prodigies, of course, on every instrument. Just look at the Yamaha School out of Japan. And there are thousands of kids who want to play music, but whether they should or not is a completely different story. But I think that when record companies pull their collective heads out of their asses, and realize that good music is what sells, and not image — image is only a small part of the equation —they will become much more profitable.

I’m about to sign a partnership with a label called “Burning City Frontiers,” and our whole thing is kind of modeled after what Jack White has done with his label. We’ll get on board with an artist for one record. We’re not going to sign you for 10 records. We’ll put this one album out; we’ll distribute it, and if we feel like doing another one with you, and you feel like doing another album with us, then excellent!

What we’re looking for is great music, period. I don’t care if you’ve got one foot in the grave and you’re a 106 years old. If you can bring it, you’re on, and you’re in! I think it’s really important to note that it’s the music, and not the people that you are marketing. Personally, I don’t know a single person who has bought a Britney Spears record for her songs, because you’re buying tits and ass, and the drama of whoever she is. She’s a novelty act.

Personally, I seek out great music. Selling songs and making real money in this industry comes from talented musicians. As long as they continue to write great songs, we’ll continue to enjoy great music. I’ve produced things in the past that I don’t like at all, but I’m schooled in music. Western music has 12 notes; I’ve recorded all of them millions of times, and there isn’t much about popular music that is a big question mark to me. It’s all in the instrumentation and what people are trying to say, and the melody line. A lot of people, especially those in the more eclectic genres, have certain definitions about what they should sound like, and how they need to emulate their peers.

Metal is one of those genres. A metal artist today will look up to Iron Maiden, and people who were popular 30 years ago. In my opinion, create your own thing, you know? Sure, borrow from the best. That’s how you become a good player. Then, when borrowing from what is considered the best — it’s really a strange thing I’m talking about now, so I feel weird — but let’s stick with metal as the example. When you listen to some of the things recorded and popular 30 years ago, that stuff is super dated. People have certain things they want to hear in their music because so-and-so was popular, and they had those weird things about them. And to my ear, that doesn’t necessarily make good songs. Good songs are made from your heart, and they appeal to the masses.

We’ve talked about artists who aren’t of a popular age or sex, for example, if you’re not a 22-year old female “hottie,” then you shouldn’t be in this industry. But it’s not the modeling industry, dude. Last time I checked, you can’t see sound.

So where do I see music going in the next 10 years? It will probably continue much the same as it is, until somebody comes across with a business model that blows away the rest of the industry and is successful. There’s such a term as “starving artists” for a reason: It’s because they usually suck as businessmen. And because of that, like it or not, artists are stuck with businessmen in some form or another. And managers, for that same reason. It’s the nature of the beast. All artists depend on their management because they have no clue about how to book a show or how to make the myriad of other business decisions that need to be made to make them successful. So we as artists need the business people. I’m sure that the business people have never heard of the term, “starving lawyer,” because it doesn’t exist!

MIM: Tell me a bit about the Masters Series Webinars that you’ve become involved in. What is the aim of these webinars, and is this something that the home-recording artist could benefit from, or should the attendees already possess a background in recording engineering and production before signing up?

Wright: Actually, Teri Doty (Editor-in-Chief of Music Insider Magazine) came to me with the idea. I had mixed a record for her husband, Billy Doty and his band, Hateshop. She had hit me up on Facebook, and asked me if I would be interested in teaching a class on ProTools. They were thinking of creating a sort of live, virtual online school, and I actually thought, “Hey what better guy than me?” I know ProTools inside and out. I use it every day, so I said, “Sure, I’ll give it a go,”, and then Teri’s partner, Hank Stroll and I started talking and going through what this would entail. I started getting ideas like, “We need sponsors. What about Avid? Avid makes ProTools. Wouldn’t they be interested in sponsoring me?”

The answer came back from Avid, and it was “no” because they wanted to do it themselves. Why would they want me to make any money teaching their product when they want to create classes for themselves, and sell a certification? So I went around and around with Avid for a couple of weeks, but then I thought, wait a minute. You know, you can read a book if you want to learn ProTools. There’s actually a “ProTools for Dummies” book out there, so I changed the format a bit on the whole thing, and now it’s called “An Introduction to Professional Record Production.”

So the ProTools class went by the wayside, and we came up with the idea for creating a class to teach a professional music production course instead. The webinar is complimentary and a prerequsite for the complete online course. The first webinar is January 31st, and I hope many of your readers will sign up.

MIM: What are some of the topics that you will cover in your webinar sessions?

Wright: Since it’s a course on record production, ProTools will be included, and I’ll show you the basics on how to use ProTools. If you have questions about your particular version of ProTools and what’s happening with it, I’ll have techs standing by that will be able to help people with their problems, should the necessity arise. But I’ll cover the whole of record production, and how you produce a record from start to finish. We’ll get into miking techniques, which mics to use in certain situations, as well as things like studio etiquette and the technical aspects of record producing.

MIM: What made you choose Nashville as your base of operations over cities like Los Angeles or New York? How has being in Nashville benefitted you as opposed to being in either of the other cities?

Wright: This is the center of music. Not only is it in the center of the country, but the talent pool here is way beyond New York, LA. People will argue with me about it all day long, but it’s because they haven’t been here — They didn’t go out 90 days in a row to see countless shows and see the interchanging of musicians, and how this bass player can play with this band who was playing country/bluegrass, and then walk down the street and play guitar in a hard rock band! And it’s that which really attracted me to Nashville. I have a bunch of friends here, too.

I love music, and I’m never going to be out of the music industry, so Nashville was a perfect choice for me. One of the things I did when I moved to Nashville to acquaint myself with the city and some of the people here was for the first 90 days, I went out every single night, and just hit bar, after bar, after bar — not to get drunk or anything, just to see what talent was here. And now my thoughts are New York, LA, Miami, Atlanta, Chicago, and Detroit — all together, they’re dry compared to Nashville. It’s amazing to me, you know what I mean? It’s like, wow. It’s not just the business end of the industry here but also an amazing talent pool of artists and bands that you just can’t get anywhere else.

MIM: Of all your accomplishments and awards you’ve earned in the music industry, which are you the most proud of, and what makes them more significant to you personally?

Wright: Probably the Grammys. They’re supposed to be the most prestigious of the industry awards, but I also treasure my platinum records. I think I’m not proud of any one in particular over the others. They all mean a lot to me, and they signify something, an accomplishment that I’ve made in my life, and when I look at my wall I go, “Hey, that’s pretty fucking cool!”

I try to not have an ego about all that stuff, and I let other people carry that for me because whenever people come to my house, or in the studio or whatever, they’re like “Holy shit, dude! Look at all these!” And I’ve got boxes of them that I haven’t even hung up since I moved here because there’s no room for them. I’m very proud of them because it took a long time to accomplish a lot of those records, but at the same time, I don’t want to flaunt it.

MIM: If you had to give advice to someone who wants to get into recording engineering and producing music, what would be the single most important piece of advice you could give someone wanting to do this for a living?

Wright: The best piece of advice I can give a musician starting out is to learn everything you can about your instrument and as a player, learn as many different genres as you can. If you’re a guitar player and you’re into metal, don’t just listen to metal. Listen to jazz, listen to flamenco, listen to anything that you can, and pull every trick that you can pull to try and make you and that guitar sound like you, an individual. It doesn’t matter if you’re a drummer, guitarist, bass player, or singer. Learn all you can about your instrument, and play it with love and passion.

Everyone is an individual in this world, and there doesn’t need to be another Mr. X. Know what I mean? We’ve already had one of those, we already know and love him. So I think some of the best advice is to be yourself, write what you feel, play what you feel, find people who feel the same things and just got for it! Study your craft, just like a good doctor or lawyer would study medicine or the law. Musicians get out there and play your asses off! Play with whomever you can, wherever you can, as often as you can. Live it, learn it, and breathe it. I think that’s what makes great musicians, and it also lets you know if you’re in it for the love of it or just the tits and ass. And that goes for producers and engineers, as well. Same advice: Learn your craft, and listen to past productions to see what’s possible. You know, one of my favorites is Quincy Jones. He’s one of the best in the world. People like Quincy and T-Bone Burnett, who keep setting the world on fire.

MIM: What aspect of your career is most rewarding for you at this point in time? What do you get off on most about doing what you do?

Wright: I think the most rewarding thing for me is seeing someone’s song go from an idea to little plastic discs, to the radio, to mass recognition — and instilling in that artist the confidence that he or she didn’t have when the artist stepped in the studio for the first time with me. And that confidence comes from artists knowing that they did it, and proving to themselves that they could do it.

What am I in that equation? I’m just the catalyst that helps them get there. You say “producer,” but as a producer I have 5,000 roles that I have to play — I’m a psychologist, I’m a mom, I’m a dad … And that’s why I refuse to deal with “problem children” anymore, because they need more mommy and daddy time than anybody else and there isn’t enough money anymore for me to want to do that.

Today it has to be more about making music than propping up your mental well-being. Do you need to be at a certain point mentally when you step into the studio for the first time? Absolutely you do, or else you’ll break down and lose it. Recording is repetitive and stressful sometimes, and those who aren’t ready for it won’t be successful. My biggest reward is to watch those artists that I work with become successful and seeing people’s dreams come true. That’s a big part of why I love doing this. I like my dreams to come true, and they have so far! So if I can help you achieve yours, that is great for both of us. Because I get off on helping people; I’m a healer by nature, so I get off by helping people do something that they want and need to do.

MIM: Gratuitous question … If you were on a desert island, and only had room on your iPod for the complete works of five bands, who would they be, and why?

Wright: Jimi Hendrix, Janice Joplin, Led Zeppelin, and Lynyrd Skynyrd with Steve Gaines on guitar and the Rolling Stones.

Author’s note: I want to thank Toby Wright for giving me one of the most interesting and enjoyable interviews I’ve ever done. It was truly a pleasure and a privilege to sit down and talk to one of the best in the business, like a couple of old friends just passing the time. I appreciate his candor, and allowing me to pick his brain for the insights into his experiences as an engineer and producer.

If you want to find out more about Toby Wright, his career and his current projects, go to http://www.tobywrightmusic.com.