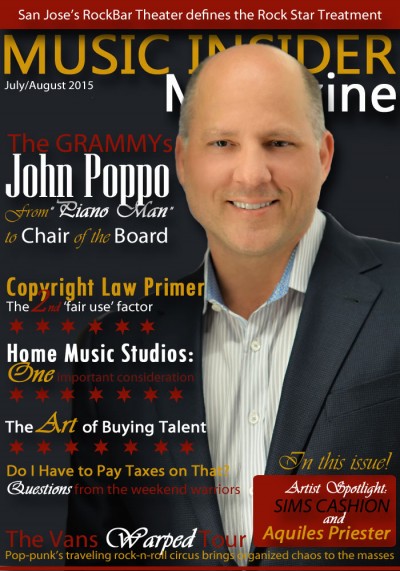

From ‘Piano Man’ to Chair of the Board

John Poppo grew up in Long Island, N.Y., and even as a very young man, he had a plan for his life. As a promising young musician, he had decided that he was going to be the next Billy Joel or Elton John. At least, that was what he told his father one day, his life’s goal as a budding singer, songwriter and pianist. But life frequently has a penchant for steering us all in some rather unexpected directions, for however exceptional Poppo’s life was destined to become, life still made no exceptions for him, and life went about its business of diverting his best laid plans.

Poppo’s story is one of a man with a focused vision, whose confidence in his abilities, while being able to adapt to changing times and circumstances, has brought him to his incredible success within the music industry. It really is a story of the American music dream.

Brian McKinny: When did you first realize that music could be a serious career option for you? What was happening in the industry at the time that caught your attention and made you want to pursue it seriously as a career?

John Poppo: Well, I love music. I grew up in Long Island, New York, a student of some great eras in music — the ’70s and ’80s, with every kind of music out there. It was pretty easy to get addicted to it. I gravitated toward learning how to play the piano at a pretty young age because it wasn’t enough to just listen to if for me, I wanted to create it. I was also a jock in high school, which was sort of a contradiction, but I enjoyed it.

John Poppo: Well, I love music. I grew up in Long Island, New York, a student of some great eras in music — the ’70s and ’80s, with every kind of music out there. It was pretty easy to get addicted to it. I gravitated toward learning how to play the piano at a pretty young age because it wasn’t enough to just listen to if for me, I wanted to create it. I was also a jock in high school, which was sort of a contradiction, but I enjoyed it.

I had a rock band in school, and I decided to get more serious about it, so in college I studied both music and engineering. While fulfilling the requirements for a bachelor of arts degree in music and becoming a classically trained musician — I played a Prokofiev concerto at my graduation- I ultimately got a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering, so I could understand the technology that was becoming a very strong part of the music. It wasn’t just about keyboards and guitars anymore. It was computers, digital synthesizers and a lot of other changes -the knowledge required for Audio engineering was also growing exponentially. So it was a balance of both creative and technical worlds for me.

When I got out of school, I came back to New York, and hip-hop was just starting to really blow up, but everyone was thinking it would be another one of those fads that would disappear quickly. Flash forward 25-30 years later, and clearly, they were wrong! I’m certainly glad I got involved in that music. Dance music was really blowing up, too, back in the ’80s and ’90s, and a lot of remix technology— where we learned how to speed up tempos and to turn ballads like “Un-break My Heart” into dance floor records — was breaking out, and I started doing remixes with DJs who were becoming producers because of their knowledge of the genre, but without a lot of understanding of the recording/mixing process. So, I was a musician and an engineer, but eventually I got an opportunity to start producing also.

Later on, I got signed to a worldwide publishing deal as a songwriter with BMG International, so I can safely say that I’ve run the gamut of doing several different careers and tied them all together, so that puts me in a really good position to be able to relate very personally and directly to all our constituents and members of The Academy (The Recording Academy, also referred to as the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences).

McKinny: Going into college, I’m sure you had certain goals you wanted to accomplish. Did your time in school have an impact on those goals, and did your aspirations and preconceptions of the industry you were about to enter change as a result of your experience at college?

Poppo: That’s an interesting question. I wish my father were still alive to answer that, because he was a lawyer, and I got pretty good grades in school, so on the day when I told him that I really wanted to be Elton John or Billy Joel when I “grew up”, I think he had a silent heart attack. Things really do evolve. I think at one point, I certainly had an ambition to be a recording artist — I was a singer/songwriter in a rock band growing up, and I was playing piano bars until 4 o’clock in the morning when I was only a junior in high school, and the like.

I went to college to get my degree, because I wanted to make a living, and I wanted to at least get an understanding of it all, even if I couldn’t necessarily do it all. There’s just so much in the process of recording, getting in the studio — making demos, making records — that you didn’t want to have to entirely trust somebody else to do. So it was nice to be able to learn to make a record from soup to nuts, to start with the genesis of it – writing the songs, doing the arrangement, playing the parts on the piano or keyboards, and then to actually record and mix it myself and produce it. It was very gratifying.

I guess if there was a part of it that evolved at all, it was just whether or not I would pursue being a full-fledged performance artist. I think if anywhere I deviated a little bit and got distracted, it was getting so immersed in the technology part that I originally thought was going to be just a backup. It became very present and prevalent in the plan, because it was more creative than I had originally realized. It wasn’t technology, in the sense of designing equipment or wiring a studio for example, not that that can’t be creative, too, but I started getting involved in the creative aspects of recording engineering and producing, using all that new exciting technology as a tool – for example, midi, digital synthesizers, samplers and sequencers and the implementation of computers.

I started paying the rent, so to speak, with the engineering and the mixing, and that was how I became good at it. And because of that, I had a career going. Everything was a stepping stone to the next dance, because I always had my eyes set on continuing with the creative side of it, writing the songs, producing the records, if not for myself, certainly for other artists — to develop other artists, alternately.

It’s funny how things shift, because the music business has a way of compartmentalizing everything, putting everything in a neat package, so I found myself with the aspiration to be a “creative,” but I got so much work as an engineer — the “go-to” mixer and engineer, everyone in the industry knew me as an engineer — so I didn’t necessarily have to go get a self-addressed stamped envelope to send out a demo. I could get any major label exec on the phone at a moment’s notice, but these execs weren’t necessarily giving me production work, because they get used to seeing you wear that particular hat, and they don’t even know you’re a musician, or a songwriter, or whatever. So sometimes you have to take two steps back to go a step forward. But ultimately, I made the transition.

I remember it was so funny — I felt like I had arrived, or at least was finally being successful in changing my professional image, when I was producing NSYNC, and I got a call from the A&R department at RCA Records, asking “When will you be done with this production so we can mix it?” RCA had someone else lined up to do the mixing of the recording, and I told them, “Wait … You don’t need anyone else to mix MY record, so don’t worry about it!”

It was pretty funny, because I had finally “officially” evolved from engineering and mixing, to producing, and I just had to laugh about it, because I ended up mixing it myself but I had finally arrived, to where some people now knew me as a producer and even composer. In the music business it takes time to build things, most of all perception!

Yeah, I’ve gone through several different evolutions, but it’s all pretty much the same. At the end of the day, I’m still making records and developing new artists, and I’m very engaged in both the creative and the technical side of the music business. I don’t think I’ll go out and do a tour as some kind of rock star anytime soon, but hey … hopefully, I’m the guy behind quite a few others who are doing it, so that’s pretty gratifying on its own.

McKinny: You spoke about labels and how you can get pigeonholed into specific roles. Did you find it difficult to shake off those labels and make the industry take notice of your other abilities, especially when you started to mentor and promote other artists and bands?

Poppo: I don’t know if it was so hard to change people’s minds as much as it was just to make them aware and take notice, or to find an opportunity to branch out into something they’re not used to seeing you do. If they get used to you being their go-to guy as an engineer, and that’s all they know that you do, until one day they see you sitting behind a piano playing or somehow hear a song that you wrote or something, so it’s always about educating them and promoting yourself in different roles you can fulfill, to transition from any one field that you are recognized in and try to become recognized somewhere else. It’s really very similar to what an artist goes through trying to re-invent themselves and suddenly do a genre of music that their fan base does not know them for yet.

You know, it’s kind of ironic, because I’ve been writing songs since I was 12 years old, and I was aspiring to be a songwriter and get involved with that “creative” process, but first I became an engineer and a producer.

Sometimes it’s really about you. It’s not so much about others but more that you have to take the time to make sure you keep yourself and your vision on path, otherwise It’s easy to get lost. I think everyone has to grow in the music business. That whole concept of the “overnight sensation” is an inside joke with everybody in the business, as I’m sure you know. It’s one very long night!

McKinny: Over the course of your career, what are some of the things you’re most proud of, as a performer, engineer, producer, or as a mentor for new talent? What really stands out in your mind as the most memorable accomplishments?

Poppo: That’s a really tough question. I don’t know if I could name one specific record, but I’m sort of a workaholic, an overachiever, a perfectionist, like so many people in the music business and the creative world, and when you’ve put enough work into something where you feel like you’ve earned it, and then you actually achieve it, it’s such a gratifying experience that even though certain things you earn in steps, you know — like if you set your mind to becoming an engineer and eventually you’re mixing a Michael Jackson record, or you set your mind to becoming a producer — while it may take some time, eventually you get that opportunity to produce an NSYNC record, or you want to be a songwriter and down the road you get to work with some major artists … I feel like I’ve set my mind to doing certain things and have been ambitious about it, and I’ve managed to hit the milestones and make some accomplishments at one level or another with the songs I’ve written or the various records that I’ve engineered, mixed or produced etc.

Frankly, getting to that point always feels good but I have also lived through a time and a music industry that was maybe in a little better shape than it is today, and managed to do okay and get rewarded for the hard work — where there are still many today who work just as hard but aren’t able to achieve that reward, because it’s a beat-up business.

So then to have an opportunity to give something back and join The Recording Academy has been a very gratifying experience, and actually that’s one of the things that I’m most proud of. Ironically, it’s the work that I’ve done that has not been for profit, during the 12 years I’ve spent on that board, and I’ve tried to help others to have the same kind of opportunities by helping with so much of what The Academy does … When I first got involved, like so many others, I thought it was just the GRAMMY show, but when I got more involved I realized, “Wow! This is just an unbelievable organization!”

Even today, our brand has become so powerful that we can raise over $7 million dollars in one night –with the help of course of the amazing and generous artists we are privileged to work with – at our Music Cares event to give to musicians in need … It’s just an amazing thing to be a part of, and to be a part of The GRAMMY Foundation, the charities and the advocacy work which we’ve managed to accomplish. So it’s nice to have gotten to a point where it’s not about bragging rights to a record I’ve made or what I’ve accomplished, but more important work with the Academy and even some of the other charity work I’ve done — I got very involved with the Tunnel to Towers Foundation, and I wrote a song called “Running In.”

McKinny: Yes! I saw you performing that song at the 10th anniversary memorial concert in New York benefitting the Tunnel To Towers Foundation with singer Chelsea Chris, and I must say that was a very moving performance — that’s quite a song, and you both played it so well.

Poppo: Well thank you! I guess that’s the frustrated performer in me, that every once in a while I have to get up to play and sing! But as you noticed, I managed to have a beautiful and very talented young lady singing with me, just in case I dropped that ball, I had some kind of a diversion, and she is an amazing young artist that I’m working on developing. I think she’s going to be a star.

It was great to see such a young person enjoying the actual music and giving of her talent, and remembering that it’s not all just about fame and fortune — it’s about moving people with your music, and it became a sort of an anthem for them. It was very exciting, because that’s the real payoff when you write a song that’s from the heart when you feel inspired, that other people get and appreciate and in turn also become inspired. There’s no greater reward than that.

It’s not always about how many millions of records you’ve sold. For me, that’s really it, the fact that the motivation actually connected with the result on that one. I didn’t get into this business just to try to make money; if that were the case, I probably would have gotten a different kind of degree, gone to a different kind of school. It wasn’t my primary motivation, like most people who get into this industry. Most people in this business have a passion for it, they’ve been drawn into it … It’s something that you need to do with your life. It’s not just about paying your bills.

McKinny: When you’re searching for artists to develop and mentor, what are some of the things you look for, besides the obvious answer — talent? And how has the industry changed with regard to how record labels view the A&R process? It doesn’t seem as if the major labels are focusing on finding and developing new talent like they used to in the past. Who do you see will pick up the slack?

Poppo: I’m looking for talent and gift, first and foremost of course, because you can teach and develop someone’s skills, but if they don’t have talent, they’ll never be what you had hoped they would be. So, they have to come into it with a certain talent or gift that you can’t give to somebody. You can’t “create” a true artist. Nobody really understands what it is, what we refer to in the business as the “star quality” or the “artistry” — where does that all come from, and how does one channel those creative things? I don’t think anybody really knows.

Most of us can recognize it when we see or hear it, no matter how raw it is or how much it needs polishing. But then there are different degrees of polishing and the development of the skillsets to support and enable the talent…the technique and tools, and I think that part is underestimated. In the old days the record labels spent a lot of time doing “artist development”. Typically maybe they’d send an A&R person down to a club in Greenwich Village in New York for example, and they’d find a talented act on stage, sign and invest in it and finally, even six or seven years later, that person might be the next Bruce Springsteen.

But in the meantime, they were primarily looking for talent, and it wasn’t about YouTube or Twitter followers per se. It wasn’t the same “business” model — it was business, but it was a creative business that could afford a different kind of risk level. So, I think people like me and the independents like myself, the management and production companies, have sort of replaced that part that is still so vital and necessary but not done as much by the labels, because it’s not really a part of their business model anymore. They can’t afford to do it on the same scale, because of sea changes in the industry and marketplace.

You have to look at it in its most basic level. If you develop 20 artists, and you spend a million dollars on each of them,even if only one makes it, as long as that one is Michael Jackson, and you sell over 50 million albums of Thriller alone at $18 dollars or so per unit retail, you could more easily afford to have a profitable business model even if the other 19 failed after taking a chance on them and spending time and money really nurturing and developing them. You have the upside to offset it. If your actual sales upside is as reduced as it is today, it becomes a game changer. — like last year, I believe one of, if not the only platinum selling album of the whole year was Taylor Swift; Platinum is only a million albums — it doesn’t give you a lot of room to take chances or spend time or money on the development side – to invest in nurturing the new and completely unknown artists based on their talent alone. You will certainly spend money on the artist who is somewhat proven and very likely to succeed, especially if they already have millions of followers on Social media and whatever else, and you can take it to the next level by doing development in terms of the promotion side, of course. But you have less room and luxury to truly cultivate the artistry of that “diamond in the rough” and ultimately have yourself the next Bob Dylan or Whitney Houston.

It’s really a shift in economics and focus but at the end of the day, somebody still has to develop the artists — to have career artists you have to have artists who are trained, who won’t melt down and fall apart on you when they finally get up on that big stage…artists with real chops who can really sing of dance or write etc. Somebody has to nurture that, and teach them and let them grow. And so for me, that’s the second part after the talent — because I know I can supply the training and the mentorship —you’ve got to find artists who also have a sense of reality and a good strong work ethic. They have to have the hunger, but they also can’t be just dreamers. They’ve got to be willing to do the work….to know there are no shortcuts…. again, it’s that “overnight sensation” thing.

A lot of fans think that these stars just wake up and step in a lucky hole somewhere and “boom,” they’re on Easy Street at the top of the charts. They really have no idea what kind of work goes into it for some of these kids to get where they are, the sacrifices they’ve made, especially a lot of the young ones. A lot of these kids are busting their butts and working very hard developing their skills in dance studios and in vocal training, performing, writing tons of songs, etc,

And if you’re looking for a young one to mentor, you have to audition the parents, too! If you want to start with artists when they’re young, you’d better make sure that they come from a grounded family; otherwise, you’ll be headed towards lots of headaches and heartaches. I mean, we’ve all seen enough of those. It’s not that hard to see a self-destructive mode coming.

If you steal the childhood away from a kid, and then they start making tons of money, and trying to be adults at 15 or 16, and working like crazy, and it’s not like they had time to go to a normal high school, the prom, or spend a lot of time developing any kind of social life or understanding of the world, and then you expect them to write a hit song??…. about what, exactly? They have no real-life experience. We need to always remember that artists are people first. The “product” we’re developing is a human being, and often a very sensitive one.

McKinny: We’ve talked a lot about changes in the music industry, but from your perspective, what have been the changes in the business you’ve seen that have made the biggest impact on the industry overall?

Poppo: Well, all I would say, because that’s such a big topic to cover in such a limited timeframe is that where the biggest, most obvious impact has been in the music industry is with the technology, much like in a lot of other industries. We don’t really have an exclusive on that. Technology has impacted our industry in a very positive way, but it’s also impacted it in a very negative way.

Poppo: Well, all I would say, because that’s such a big topic to cover in such a limited timeframe is that where the biggest, most obvious impact has been in the music industry is with the technology, much like in a lot of other industries. We don’t really have an exclusive on that. Technology has impacted our industry in a very positive way, but it’s also impacted it in a very negative way.

It’s made some things difficult, because it’s tough to sell what some people can so easily get for free. I mean, you can’t open up a grocery store and put up signs that say, “Please proceed to the cashier for payment, if you’re so inclined.” It just doesn’t work, if it’s available for free, how do you “sell” it? And now it’s not even necessarily just about the concerns of “piracy” — you have all these streaming entities introducing new challenges to the business model too and they are entirely legal.

You didn’t have streaming to worry about 10 or so years ago. Gong back some years , you had technology challenges being introduced from companies like Napster threatening sales but of course that was illegal and it got shut down,- though piracy far from went away. But today, it’s like a perfect storm. Even Apple who came in to “save the industry,” by making it easier to “buy” music online and maybe helped reduce the inclination to “steal” the music, still effectively turned it back into a “singles” business, so then you were selling 99-cent singles instead of $18 CDs.

McKinny: When I was a kid growing up in the early seventies, I’d go to the store with my folks or my friends, and we’d buy 45 records, because that was what was hot at the time.

Poppo: Right! And you saw just how they got out of that business, and moved to more albums, on vinyl first of course, but then there was the advent of cassettes and 8 tracks and ultimately CDs, … Just how many times did you buy those same albums all over again in a whole different medium?

But now it’s digital files, and it’s changed again but in many ways for the worse, so the record labels , trying to stay alive moved onto 360 deals, tapping into other forms of the artists’ revenue. everything has shifted, and it’s still trying to find its way, I think. But I like to look at the glass as half-full and I don’t think it’s a dying business; I think it’s a changing business for sure, and it’s going to be tough to wrestle with some of the undeniable facts of technology that make it very difficult for it to be profitable but the good news is there is more demand today for music than ever before. We just have to keep adapting to find the new “business model”.

You know, when we were kids, they incurred the expense to make expensive videos to promote records and then you’d sell the records. It was expensive, because nobody bought videos back then. Those were free, but then you’d sell the records.

Now, in many ways, today we make the records as a promotional tool to sell the brand, the celebrity of the artist to be able to tour, endorse things and sell t-shirts and merchandise etc. But again, the good news is that there’s more music out there now, being consumed and in demand today, than there ever was. It’s just about figuring out how to monetize it and keep it a viable commercial property, and a lot of that has to do with why the academy is so active in advocacy initiatives — fair pay for all creators, revenue from terrestrial radio, performance royalties and all the various things that they’re doing with their voice that I’m so excited and proud to be a part of, because music is an intellectual property that has to be respected and protected from a legal aspect as well.

The same way you can’t just walk into an art gallery and say, “Hey, I like this one!” and take a painting off the wall and then walk out the door, you should have to pay for music like anything else that is of value. And I personally applaud artists like Taylor Swift for standing up and trying to get that message out there. I mean, you’re enjoying it, and there are myriad different industries profiting from it as well, so it certainly has value— just take a look at the valuation of Spotify as a company The value of the company is predominantly predicated on the music it provides. That’s not to knock Spotify by any means — it’s using today’s technology to provide a service to the public that people value and enjoy —but the point is that there is clearly a generally recognized, huge monetary value to the music that it and others deliver and I, like so many others, including the Academy, am simply committed to assuring that the actual music creators be properly and sufficiently compensated for the product that they are creating, which clearly has real value.

McKinny: Let’s talk some more about The Recording Academy. How long have you been involved with it and in what capacities have you served in the past before being elected as the new chair?

Poppo: I’ve been a member for about 15 years. I was on the local New York Chapter board for three years, and then I spent about 10 years on the national board as a trustee before becoming the vice-chair, and now the chair. So I’ve been on the national board of trustees for 12 years or thereabouts, and in terms of what I’ve done for The Academy, or what I’ve worked on — pretty much anything that they would let me, for the most part, and that I had time for. I’m in it hook, line and sinker as far as what The Recording Academy represents and what it’s doing, and I’m proud to be part of it.

I’ve served on a bunch of its committees — the awards and nominations committee, planning and governance committee and quite a few others. Now I’m the chair of the Board of Trustees, which is an incredible group of people and representatives from the 12 chapters around the country, a very illustrious board of accomplished professionals who gives up their time to work with The Recording Academy, and I’m honored to be leading it. So I’ve been involved for quite a while and hope to be for quite a few more years, because they do just such amazing work.

McKinny: As the newly elected chair of the Board of Trustees of The Recording Academy, what is your vision for it and what are you looking forward to the most with regard to putting your mark on any specific aspect of it, be it professional development, cultural enrichment, advocacy or the education and human services programs which the academy supports?

Poppo: Not to be evasive, but I have to say all of it, because it’s all pretty much equal. We have something that our CEO developed called “The Four Pillars” —education, advocacy, awards, philanthropy and charity. We’re doing them all between our sister companies and ourselves, pretty much equally, and making great strides in all of them. My wish is to continue to raise the bar more to do even better.

I’d like to see us make more headway on the advocacy initiatives and I want to be able to raise even more money to help even more people, and to foster education on every level. We want to continue, of course, doing what we do with awarding and recognizing excellence and being the organization whose awards are voted on by your peers – other music creators who have to be established voting members, who are in the industry also. So it’s not any one particular thing really, and that’s my job, to oversee the whole thing — to lead the board in all of our current initiatives and to work collaboratively with our CEO and president, our “fearless leader” Neil Portnow to create a further vision for the future of The Academy. But I think the vision is pretty well on path. Now, it’s more about executing and implementing that vision to keep the momentum going.

I would ask that if you write anything in your magazine, it’s just that anybody and everybody who is eligible to be a member of this Academy should absolutely join! It’s just the best deal in town, and to be working in the music industry and to not be part of this this community, this family, is just crazy.