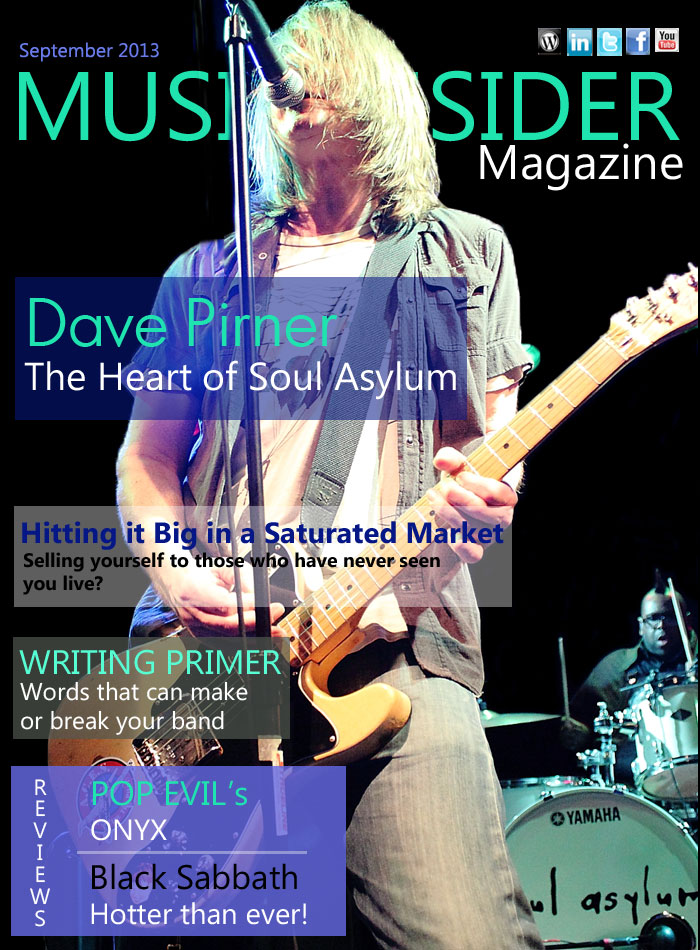

Most people don’t know that Dave Pirner started his career as a drummer in a punk band. A native of Green Bay, Wis., he moved to Minneapolis, Minn. as a teenager. By age 20, he had started playing drums in Loud Fast Rules, together with Karl Mueller (bass) and Dan Murphy (guitar) in the Minneapolis sub-punk scene. When Pat Morley joined the band and took over on drums, Pirner moved from the back line to singing and playing rhythm guitar. After Morley was replaced on drums by Grant Young, the band changed their name to Soul Asylum.

During the early 90s, the band garnered something of a cult status from fans in the Midwest, and by 1992, Soul Asylum began to achieve commercial success with the release of the first two singles off the “Grave Dancer’s Union” album, “Runaway Train” and “Black Gold.” Both singles experienced heavy rotation on U.S. rock radio stations, as well as on MTV and VH1.

Pirner’s music was less identifiable with the grunge scene emerging at the time than his personal appearance was, with his blonde dreadlocks and disheveled manner. His music was less dark and angst-ridden than most grunge music that was prevalent at that time. Soul Asylum’s music was more upbeat, mainstream than contemporary releases, helping to separate the band from the rest of the pack.

I recently spoke with Pirner at great length from his home in New Orleans about what lured him from Minneapolis to New Orleans, how he and his bandmates dealt with the loss of their friend and bass player Karl Mueller to cancer in 2005, and the eventual re-start of Soul Asylum with the current roster of players.

MIM: Why did you choose to move to New Orleans?

Dave Pirner: It was all about the music. I had been trying to make my way in Los Angeles and New York City, and I think that that’s where I got the itch to be somewhere more multicultural, but I was a little too “small town” for LA or New York. And so, New Orleans really seemed to be that place — a bit of the outside world, the whole mess that is American culture.

It’s just sort of dirty and full of funk, and full of stuff that Minneapolis was lacking. Having grown up there, it was just so clean and white, middle-class, and I just fell in love with all the different elements of New Orleans. I was not put off or afraid about anything; I was just fearless. People told me, “Don’t go into that neighborhood.” I said, “Well, that’s where I’m going, because there’s a club there that has a trumpet player I want to hear.”

I’ve always had a great experience when people tell me not to do something or not to go into some place they’re afraid to tread because it’s dicey. I have been fortunate to be on the road for 20 years, so before, I didn’t care where I lived. I was used to the company of strangers, and I was used to having to make my way without knowing anybody.

New Orleans is a perfect town to suck in somebody like that, because not only is it a tourist economy from the top side, it’s such a rich economy from the down side. From the panhandler on the street, to the guy sitting next to you at the bus stop who strikes up a conversation, each has the same approach. It’s a transient town; it’s the city that welcomes you. It has that sort of Portland (Oregon) element to it, where it’s just full of crazy people who are kind of heading somewhere else, or maybe they don’t really know … There’s that part of it; we’re all immigrants or share a common thread. And last, but not least, it’s much more desegregated than where I grew up, so that had a huge impact on my music, and just about everything else.

I was talking to a Haitian cab driver the other day, and I asked him, “What’s up with the voodoo thing in Haiti?” He said, “My friend, every country has its own voodoo.” I said, “Okay!” As I was getting out of the cab, he asked me, “What did I tell you about voodoo?” I looked at him and told him, “Every country has its own voodoo.” He goes, “That’s right.”

That’s where I glean some of my most important information, talking to somebody who’s actually from some place, and not from people who just think they know what they’re talking about! This town is more than about just jazz and voodoo, but those things add to the flavor. There’s an amazing amount of syncopation, a rhythmic flow that comes out of here that the children come up with, and it’s deep within the second line beats, and for people from outside of New Orleans, it starts to turn into a kind of Bo Diddley-type of situation, which is really interesting, but it’s in the numbers of the syncopation that opens up the possibilities for me, basically.

If you watch a violin player perform a classical piece at a speed you cannot understand, it starts to blur together, but it’s all math. It’s the same thing with the way you play a tambourine in New Orleans. You don’t play a tambourine like that anywhere else. It’s all just rhythm, and it’s a beautiful thing. It’s beyond me that it’s such a hub, here in New Orleans, for all these different rhythms and beats, but it’s definitely where I want to be.

MIM: How long had you played drums before you decided to move out front, pick up a guitar and start singing?

Pirner: I think that I’m probably one of those guys like you were, who took out all mom’s pots and pans and put them out on the floor like a drum set, and I think that’s kind of symptomatic of folks like us. As I was growing up, I remember my parents getting me out of bed whenever a drummer came on the “Johnny Carson (The Tonight) Show,” and it was usually Buddy Rich. From the get-go, it was apparent to my folks that I had an interest in the drums. I had the obligatory toy drum set that I begged my parents for … When it came time to pick an instrument for school, I picked the trumpet, and I started that in second grade. But still, I always thought the drummer was the coolest person in the group! After I realized the trumpet just took too much discipline, and I would never be very good at it, I decided to pick up the “slacker” drums and the electric guitar! I understand it when some of the heavier musicians in New Orleans give me the business, “Yeah, but you’re playing that rock ‘n’ roll shit …”

MIM: Without the blues and jazz, there would be no rock ‘n’ roll …

Pirner: I’m glad to hear you say it, because it’s not always easy for people to comprehend, but it becomes very apparent in New Orleans. That’s just one more reason that I like it here, because you can’t contest that information, because it’s like, “Oh, that’s right … And then you have the gospel influence, the Caribbean influences, and then you head due north, and you have Memphis and Nashville — it’s all very laid out.

MIM: It’s all geographically oriented, isn’t it? You start out with the jazz and gospel influences in New Orleans, then move on up the Mississippi from the delta to Memphis, and then on up to St. Louis, and then to Chicago, and then the influences spread east and west; but the influences are rooted in the music coming out of New Orleans.

Pirner: Yeah, I’ve been trying to explain that to people for years, but I like to be where it’s happening, because it’s living history in my mind, and it’s still happening. And I have the same feeling when I go to Memphis, whether or not you’re using an upright bass, or whether you sound a little more country than rock ‘n’ roll, or whether you sound a little more black than white. It’s all still evolving in a strange kind of way. You don’t really know how it will influence things until something strange and new happens. I think that once you stop being a student of the music, something terrible happens. Learning in the arts shouldn’t ever stop.

MIM: When you first started out as a musician, who influenced you musically? And was there a specific moment in your life when you knew you’d do this for a living?

Pirner: It depends on how far back I go, because when I was playing trumpet, I was really into Maynard Ferguson, because he could play the highest notes — like admiring the guitar player who could play the fastest, it was all physical. But later on, I started discovering people like Miles Davis. And then, I had this situation where I was the first-chair trumpet player, whatever that means — played all the melodies — and the second-chair player was the brother of my teacher. So, the second-chair trumpet player was better than I was, and I knew it. But I didn’t give up my chair; I just went along with it. It was because I was flashy, and for some reason the conductor could better hear me playing, probably because I’m more obnoxious than the guy next to me who was really good.

One day, the second-chair trumpet player, I can’t remember his name, he brought in the Jimi Hendrix record, “Are You Experienced,” and said, “My brother thought you might want to borrow this,” and that’s when everything changed for me. I took it home, I listened to it, and I thought, fuck it, I’m going to play the electric guitar, because I’m really tired of pretending that I don’t. Because I had to play music in a legitimate form, that lead to starting “The Shifts” with my friends, to playing at First Avenue, and at 7th Street Entry in Minneapolis, which led to the guys in Loud Fast Rules, and to Soul Asylum.

I think the pivotal moment for me, and trust me on this — I’m still in that chair; I still do have a moment every day where I think, shit, maybe I should get a real job. I’m not joking. I wish I was kidding — but I had a job as a short-order cook making fries and burgers at a bar, and I called my boss from Green Bay, because I had a gig there and told him, “I’m not coming into work tomorrow, because I’m in Green Bay,” and he said, “Well don’t bother coming in.” So that was it, I was stuck with Soul Asylum in Green Bay, I didn’t have a job, and now here I am (in New Orleans). It wasn’t a great job, but it was a steady income. I started thinking, “Well, I can always get another job, but maybe this is some sort of a sign.” There wasn’t a lot of love lost.

MIM: Kevin Smith is one of my favorite movie directors, and Soul Asylum was asked to contribute a song and ultimately shot a video for the soundtrack to his indie cult film, “Clerks,” back in 1993. You also contributed a song to the soundtrack of the third Jersey film, “Chasing Amy.” How did Smith and you initially connect to work on his “Clerks” project, and what was it like at the beginning of both Soul Asylum and Smith’s careers to work on those projects together?

Pirner: This is so weird, because I had a dream last night that I ran into Kevin, and I said, “Hey, man, I saw ‘Red State!’ It was great!” And he looked at me like, “Oh God, I don’t like that movie …” That is so weird that you just brought up his name!

But it does come up. We brought the song “Can’t Even Tell” from “Clerks” back into the set, and depending on where we’re playing, I just go, “Hey, has anyone seen the movie, ‘Clerks?’”

You can’t really find a crowd of people who haven’t seen “Clerks” or heard of Kevin … This is so weird, because I just watched a couple of scenes from “Clerks” two days ago. I was just messing around with my movie collection and I thought, I’m going to put this on and watch a little of it, just so I can see if it’s as funny as I thought it was back then, and I was laughing out loud pretty quickly.

“Clerks” and “Chasing Amy” were just a thrill, and I’ve been wanting more work like that, but I’ve concluded that I would have to live in Los Angeles to get that kind of work, and it’s a price that I’m not willing to pay. But man, did I enjoy working on those movies. Believe it or not, I got the job for “Chasing Amy” while I was at a party and (movie producer) Harvey Weinstein was there. He was the head of Miramax Studio, I was introduced to him at this party, and he said to me, “Oh, you did some work with Kevin (Smith), didn’t you? We’re going to make Kevin’s next movie, and you should do the music!” And I thought it was all just Hollywood party talk, so I just said, “Oh yeah, that would be great!” and I thought nothing more of it.

Much to my surprise, first thing, next day, I got a phone call from Harvey Weinstein’s office, and he’s going, “Alright, so you’re going to do this, right? We’ll call Kevin and put you on the phone with him …” I was excited, and yelled at the phone, “Yeah, man! I got the job!” Harvey said, “I know, it’s awesome!”

So Kevin came out to the studio to check out what I was doing, and I told Kevin, “It’s your movie, you’re the director, and I will take the music out there if you want to. You don’t have to worry about how I feel about it.” Kevin asked me, “Are you sure? Are you sure if it’s okay if we just have no music there?” I told him, “Kevin, it’s your movie, man. Of course, it’s what I’m here to do, which is to accent this movie with music in the way you want to.”

It was great, and I really don’t remember how the whole “Clerks” thing came about, except that I think when he was looking for bands to make music for it, our band’s name came up, and then they decided to make a music video for our song to use as a promo for the movie. I was a hockey player growing up, we all understood each other’s sense of humor, and it was fun to make that video. I think I will always be able to identify with Kevin’s sensibilities; he will always be a sort of contemporary orator for me, if you will. I also love comic books, and the whole thing! We have a lot in common, and I hope I get to work with him again someday.

MIM: There was a six-year hiatus for the band after suffering the loss of your friend and bass player, Karl Mueller to his battle with cancer before you finally released the album, “Delayed Reaction” last year. It’s now September 2013. Why did you choose to release a series of four new EPs so soon after the release of the last album?

Pirner: When we were making the record, “Silver Lining,” Karl was still alive. The record came out, he’s no longer alive, and once again, we’re sort of swimming in … It’s not really desperation, and it’s not indifference, it was a kind of malaise where we were all sad, feeling like what’s the point? It was verging on feeling sorry for ourselves, but the second you start going there … Michael (Bland, drummer) pulled me up by the bootstraps and said, “Come on, man! This is important music, and you need to be out there to play it!”

It was the sort of thing that I needed to hear, because it made me think, “Shit man, if you’re with me, then I’m in!” I like to use Ron Burgundy’s, “News Team Assemble!” “We’re right here, Ron…” There’s a little Anchorman reference for you… (Laughing) Sorry about that!

But it really is about all those clichés that you can have fun with if you don’t take things too seriously. But when you’re in that position, where by any means necessary the show must go on, and this is what we do, and all that shit — It’s all very dramatic at the time, but it’s also attaching a whole bunch of importance to something that could either exist or not. And if you attach enough importance to it, it survives, and you carry on.

MIM: The new EPs contain covers of some select classic tunes as well as originals. What was the inspiration for this unique approach to marketing four separate EPs, instead of releasing them all together as a single LP?

Pirner: It’s funny, isn’t it? The reason I think it’s weird is because we put out a record of original material after people going, “It’s been three, now four, now five years, now oh, someone died, and now someone put out a solo record, or whatever …” And in the meantime, the industry is doing what it’s doing, and we just started recording a cover now and then, just for the hell of it. It was really a situation where Michael Bland, who is a large black man with a Mohawk, said, “C’mon man, bring some of that hard-core punk rock! I’m gonna play that shit!”

I sat there thinking, I can’t wait to hear Michael play this. Because there were just so many terrible drummers out there back then, and so many just blurry, stiff beats, that didn’t really have anything to do with anything other than just trying to be as angry and aggressive as possible. That’s when I thought, “what if the music’s in the hands of a man who can really handle it? “

That’s how it went, and it was exciting for me. I was like, “Holy shit! It’s the best drummer ever playing these songs, and he made them sound like they should have.” I’m a drummer, I love Michael, and I love what Michael does. And between the two of us, it was, “Well let’s try something really radical, like the Dead Kennedys,” and he was like, “Bring it on!” And afterwards, I asked him, “Well, how’d you like that?” Michael said, “Whoa, shit, man! That was fun!”

It was that kind of thing, where we explored the recent history of brutal music to see which parts of it he would destroy more than anyone has destroyed them before. It’s part of trying to bring that element of total abandon to the music in a way that’s not coming from a 17-year old’s perspective, but brings that vibrant thing that makes it so shocking.

MIM: Michael Bland is an impressive presence. I’ve never seen a big guy like him move the way he does behind a drum set. He puts a lot of joy in his playing and seems to be a very emotive player.

Pirner: Oh yeah, It’s magical playing with him. I feel like I’ve spent my whole life trying to find this dude, and he was in my back yard! I mean, I did move to New Orleans looking for a drummer. I just figured that if there was a drummer to be found anywhere, it would be here. I don’t really know how to say it, not that the essence of it is just hitting ‘em hard, but nobody hits the drums in New Orleans as hard as Michael Bland. It’s just part of his rhythmic jazz vernacular to beat the shit out of the drum set, and it’s something that’s understandable as a technique. It’s not really a part of what goes on in New Orleans; you don’t really need to hit them that hard here.

But yeah, you do! If the guitar is that loud, which of course, nobody has a Marshall stack in New Orleans, either … It just works out that everybody has to play at the same relative intensity, and Michael does that. When he auditioned for the band, it took about two minutes for me to go, “Holy shit! Here he is! This is the guy I’ve been looking for my whole life. Here he is!”

And it just breathed a whole bunch of new life into the band, and I was just talking about how great it was that Karl and Michael got to play together for a while before he passed and things like that. I went through a whole lot of trouble making records, and then getting Sterling Campbell in the band, so it’s a big deal because Michael is such a real key player.

On a record I’m producing down here, I just had a different drummer come in, and I walked out of the session going, “Good drummers make good records.” It makes all the difference in the world, because if you don’t have a good drum track, you’re fucked. You may as well stop right there. That’s the kind of attitude I have. The music needs somebody as good as Michael, someone who throws down.

MIM: You have changed the way Soul Asylum records its music, going from the more traditional and expensive recording studio marathon sessions to more of a home-grown recording experience, going so far as to build a complete studio in your house outside of New Orleans. How has that change affected you, as well as the kind of music that you and the band make these days? Has it changed the dynamic of the band’s sound by not recording it all together at the same time?

Pirner: I think it has everything to do with the players, and once again, I can go straight to Michael Bland and say that man walked into the studio and replayed a drum track that blew my mind. I’d never heard anybody do what he did before. He just has the perception that allows you to move any way that you want to, and he’s a studio rat. He’ll just get in there, and he’ll lay down a drum track, and he’ll listen back to it, and he’ll go, “Hold on a second,” walk back in there and redo it even better, and then come back and listen — and an eyebrow will go up, and then he’ll go, “Wait a minute” and go redo it again. And every time, it just gets better.

To me, the first track was better than anything I could’ve imagined in the first place! It makes all the difference in the world if you lay down a rhythm track and send it to somebody who’s in another part of the country. You don’t want to send a shitty rhythm track anywhere. So the way we’re doing things now has opened up these possibilities to shift time and be shape shifters in a way that we couldn’t have before.

You can spend a lot of time and waste a lot of breath on analog or digital, and all that, but I saw a fairly modern way of recording coming when I was in a very expensive studio and had rented a ProTools system, and there I was sitting in King’s Way (Recording Studio) with all this beautiful analog gear, and we were huddled in a corner around a computer, and I just thought, “This is ridiculous. This doesn’t make any sense at all, and the only way I’m going to make sense of this is to learn ProTools, which I did.

And now, I just sit around and have that some old argument about how much I miss analog tape, and how much I miss the sound of this, and how much blah, blah, blah … At the same time, I’m taking advantage of every single situation that digital recording presents because it’s … how should I say … it’s a lot easier to send a drive through the mail than a reel of two-inch tape. If you send a tape reel, you don’t know what will happen to it along the way. I still remember people getting on planes and sitting there with the two-inch tapes on their lap, because they were so afraid something would happen. I just spent all day yesterday packing shit up, because I don’t trust any of this technology. But once again, you go to war with the army you have.

MIM: I’ve been listening to the first four new songs that you’ve posted on your band’s website, and I think that they’re all very good, but the one that sticks in my head the most is the song, “Close.” What was the inspiration for that song?

Pirner: The rhythm track is a really good example of when my brain started to shift to a second-line mentality and started to embrace all the polyrhythms of New Orleans, to a point where it went a little bit deeper than the average rock ‘n’ roll thing, and I was trying to get that rhythmic feel in there, with a guy from England, a guy from New York and a guy from Minnesota, and it became a sort of melting pot. By the time I added the original acoustic guitar back into it, it wasn’t really translating very well. I could tell exactly where the rhythm went one way and where it went another — and it came out in a way that I liked it, but it was a real bitch to get it there. I remember listening to that track and going, “Nope,” and then starting again, and somebody else would mix it, and this, that and the other thing, and finally I was able to say, “Okay, now it’s all right.”

So it was a real arduous track, and I think it was the last track that I was trying to get on the record before we started the record over! (Laughing) I’m not sure which part of the song you’re digging, and I don’t know what we’re posting on our website half the time, but I can tell you that, Justin, the guitar player, really wants to bring “Close” back into the set list, and we just played it acoustically the other day, and we’ll probably be playing it in the live sets eventually.

Honestly, I take all these things into consideration, and I have you to thank for that also. You know, I’ll be wandering around after a show, and someone will come up to me and ask, “How come you didn’t play some fucking song, and if I hear it three times, I’ll stop and think, oh shit, I just went through three different states, and three different people all wanted to hear “Close.” Let’s put that back into the set.

And that’s cool, you know? I like that part of it, hanging around after a show and getting feedback and having a face-to-face conversation with people who tell me exactly what they want to hear. Instead of taking a survey on the Internet, surveying the people who actually showed up at your show, which shows me that they’re more dedicated to the music and it’s good to take queues from people who really follow the band. I’ll be more interested in what somebody says after the show that I saw in the front row singing along to every other song, than just some random guy who may not know anything about the band.

MIM: On the flip side, do you ever get tired of playing certain songs? I mean, there’s always the “Freebird” guy in the crowd.

Pirner: Over the years, I’ve gone from “Okay, pal. It was funny 20 years ago,” to now I’m just going to play “Freebird” whenever somebody yells out “Freebird”! How do you like that? And it really works. Suddenly people stop yelling out “Freebird!” if you just fucking play it, and the person in the audience who yelled it will get the stink eye, not me. There is no other way I can fight back. During a show, I can’t go, “Fuck you! Don’t yell “Freebird!”

Yes, there are the obvious choices, but do I get tired of playing “Runaway Train?” Honestly, the answer is no, I don’t. I’ve been through all the jokes, and I stopped playing it for three years, and enough people came back stage and said, “We traveled 500 miles and spent $300 dollars to see you guys play ‘Runaway Train’ and you didn’t play it,” or the ever-popular “I brought my two-year old infant so we could bond on ‘Runaway Train’ and you didn’t play it” … And I’m like, “Oh well, I figured I shouldn’t play that song because I wanted to challenge the audience,” or whatever.

And by the time I’m done with that explanation, I could’ve just played the fucking song! That’s the gist of it, you know? It’s three minutes and 40 seconds of playing something I really believe in, and I’m still not going to play it because I’m trying to challenge my audience, and my own ability to out-do myself by coming up with a song that’s even better, or whatever the fuck it is.

You go into an Irish bar, and there’s a sign that says “Danny Boy — 10 bucks” because the dude is tired of people yelling for “Danny Boy,” So give me 10 bucks, and I’ll do it.

I mean, that’s kind of a joke, too. So, no … I’m just glad I’ve got a gig, and if it’s a gig where people are there for the fireworks after the show, fuck it. They’ll all go “Hey, ‘Runaway Train,’ we know this one! Yay!” And I think to myself, oh shit, this is what happened in Ft. Lauderdale, where I played something off of the top of my head, which I believe was “May the Circle Be Unbroken,” and everybody starts singing along, and I just thought, holy crap, I didn’t expect that to happen! I didn’t know they’d know that song, but you just make the best out of every situation.

We played at the Seventh Street Entry recently, a little homecoming show at this little punk rock club we grew up in, and we didn’t play “Runaway Train,” there was no need to. So I think it’s possible to play in front of crowds that are such hard-core fans that they don’t need to hear “Runaway Train.” But still, some of those people want to hear it, too. I really don’t get tired of playing, period. I’m just glad to be playing.

MIM: What can you tell me about the LP Tour with Big Head Todd and the Monsters, Matthew Sweet, and the Wailers? That’s quite the lineup, and I’m curious as to how that came about; also, where can we find you on the road this year?

Pirner: The whole thing was, what are we going to do this summer? We saw what was going on out there, what was available, then we put it to a band vote, and the band wanted to do it. My angle was I’ve already toured this record, and so it’s not something that I haven’t done already, and it made me wary — What is playing an LP from beginning to end all about?

Cheap Trick was the first band that I remember doing it, and I know that Weezer did it, too, as well as a couple of other bands. It seemed like, all right, now it’s not just a fad, it’s something that bands are doing, and people enjoy seeing. So I guess while we’re releasing things available only on the Internet, in a way it makes sense to go out and play something that used to be called an LP — the thing that used to be the vehicle by which people got their music, and now that that’s not such a big deal.

It does always seem to go in a circle. The Internet has become the new English “Top of the Pops,” and this is the answer to what an LP used to be; it’s a piece of history, somehow, instead of a just being a trendy fad to go play a whole LP live.

It’s like, “Oh wow, all this music was on a record, and you could go to a store and buy it.” The record had a beginning, middle and an ending. The whole idea behind it was you were giving people a body of work, something called an album.

Now, people buy songs piece-meal, and I think they’re missing out on that, so the LP Tour and tours like it bring people back to a time when you bought an album, listened to it from beginning to end on both sides and were able to understand what the artist tried to convey through the entire work and not just a song or two you buy from iTunes.

The Internet cannot be more singles driven. I’ll ask someone, “What other songs do you like by that band?” and he’ll go, “They have other songs?” So then, I’ll take that kid to a record store, I’ll buy him a CD, and he’ll say, “I don’t have anything to play this on.”

The exciting part of playing a whole LP is that those tunes would never make it into the set list of a regular show. Packaged this way, people will hear them, and that’s always interesting. It’s always a welcome opportunity to play something I have written in a context where it hasn’t been played before.

As weird as that seems, it’s like the band went on stage around the time we were recording “Grave Dancer’s Union” and played everything on the record. I mean, it just never really happened, so that part of it is kind of cool. Now, it’s being performed as a live piece, and we did it at First Avenue, and if that had not gone as well as it did, I wouldn’t be doing this.

It was surprisingly fresh, and just different from what I’m used to doing, and no matter what, we have to end with “The Sun Maid,” which is the slowest, prettiest thing ever, completely the opposite of what I’m used to, you know? Soul Asylum ends our shows with a bang, but the record ends with a very soft, very quiet, pretty song, which is kind of a weird thing, but we made it work in Minneapolis by bringing a string section on stage, because there’s a string section on the record.

Over the summer, we won’t have the string section, so there are little details like that which we’ll have to address creatively. Again, that’s the huge difference between me standing here in my ProTools studio going, “Well I can do anything I want musically, and then I can fix this,” to being in front of a live audience and just standing there, saying “Do something!” I won’t stand up there trying to get my programs sorted out, because that’s not very entertaining for the audience or me.

MIM: In a live performance situation such as you just described, have you ever used backing tracks or sequencers for parts like that, or do you just leave those parts out? Is that something that you’ve had to deal with before?

Pirner: Well, we’ve never had a problem with it, and that’s partly because you take that aesthetic in the studio and you say, “Well shit, we can’t do this, because we won’t be able to do it live.” So it hasn’t been a problem, and I don’t expect it to be a problem. It is kind of crazy, because what used to be Milli Vanilli is not even a consideration anymore. I remember it happened to the Electric Light Orchestra — they had some of their strings on tape, and people really made a big deal out of it and came down hard on ELO. They even have orchestra in their name, and they clearly don’t have an orchestra on stage, so you’re obviously listening to more tracks on the record than they’re able to produce with six dudes on stage!

It’s not really for me to judge, it’s just weird. I’ve gone through an evolution from the first time I saw a band on stage and some noise was happening that nobody seemed to be playing, which really alienated me, to that being somewhat normal. But I still like to sit in front of a jazz trio in New Orleans, with three guys playing, and I can listen to all three of them individually or as a group. There is no smoke and mirrors going on, which is another reason why I moved to New Orleans. Here you can get that intimacy with great musicians and be up close, and have that amazing experience that can never exist on the Internet. Maybe someday in a perfect world, I won’t have to tour anymore; I can just send my fucking avatar out there, but in the meantime … (Laughing) I’ll have to do it!

MIM: What’s it like for you to be out there, still making records and touring after more than 20 years? Did you ever think when you started out that the ride would keep going for as long as it has for you and the band? If you had to point to one thing, to what would you attribute to your longevity in this business?

Pirner: Besides all of the things we’ve already talked about, it really is the ability to deflect adversity and to laugh in the face of the entire situation. If you can’t embrace the absurdity of it, you can’t get into the sort of surreal angle that will not always make sense, and it could be the most horrible thing you’ve never imagined … You have to let things go like water off a duck’s back. You have to deflect it; you can’t internalize it, because then your goose is cooked. You have to go, “Ah fuck, my heart’s been broken before, so I can’t re-break this heart. I’m going to make music, and I don’t care if anyone likes it or not!”

That’s how I started out. I think my disposition is ultimately what helped me the most, not all the trumpet lessons or all the horrible punk rock I laid on people, and without reservation with a “take it or leave it” attitude. Sometimes the joke was to clear the room. We’re not going to stop playing until everyone leaves, so fuck you! That kind of thing. We hate you, you hate us, let’s have a party!

Whatever you call it, it was this thing where we were just starting out, we knew we were terrible, and it was part of the punk-rock ethic, and it just sort of stuck. And to come from that, I’ve been spit on, you know what I mean? It really is something that stays with you, and I think it helped me quite a bit, to be able to laugh at just about anything you can throw at me.

I’ll think to myself, “Shit, you think that’s bad? I’ve taken a shit in some of the worst punk-rock toilets in the entire world; I’ve played in clubs with some of the worst PA systems imaginable, and played on beaten up, out-of-tune guitars. It doesn’t faze me too much because it’s all part of the job, and it doesn’t change. Unless you embrace that, you’re pretty much fucked, because you’re on a one-way ride to where it stops getting better and better, and then you quit.

That’s what happens to a lot of people, so ultimately the answer to the question is music. I need to be making music. It’s a huge part of my life; it’s what I do, and when I make music, it feels like a privilege or a gift. There are a lot of reasons why people are right when they tell me, “You know you can’t do that.” I’m like, “I know, it’s not making any money, it’s making everybody miserable, but I want to do this. Down the road somewhere I’m gonna be glad that I did.”

You get there eventually. You’ll show up, a show goes so great, and you say to yourself, “Now that’s what I was talking about! That’s why I got into this! And it’s also the reason why I went through the last month of misery to get to this.”

That’s the way it’s always been, and the way it will always be, and if you can handle that — it makes you kind of crazy, I’ll give it that — but you have to be sort of crazy to do this in the first place.

MIM: Is there anything you have a great desire to do that you haven’t done yet, some project, or personal goal that’s lingering out there for you to accomplish?

Pirner: Well, I wanted to sing in a big gospel group, and I did that. I wanted to play in China, but then someone I know came back from playing there and said, “Man, everyone in China is so Chinese!”

What the hell is that supposed to mean?! It wasn’t the answer I was looking for, you know. (Laughing) I want to play in Russia, I don’t know why. Most of the time, it’s just about going somewhere Soul Asylum hasn’t been, lay the Soul Asylum thing on them and see how they react.

Beijing and Moscow are two outposts I’ve never been to; we’ve never played in Africa, so I would like to do that. You know, these could be those “Be careful what you wish for” kind of situations, but a lot of things like playing at the White House or winning a Grammy and all that stuff were way beyond anything I had dreamt of and weren’t really in my sights. They weren’t even considerations, because I didn’t get into this to do a lot of the things I ended up doing but were kind of exciting, like those “wow, how did I get here?” moments. It’s cool in that way, but when I think about it, I just wanted to get a gig in Madison, Wis., then go to Chicago and then New York. From there, to LA, and to England … That’s the road I’ve traveled.

MIM: Speaking of the road, how are you handling touring these days? Is it something you look forward to, or is it a sort of necessary evil? I know Soul Asylum has always had a reputation as a band that has to be experienced live because of the great show you put on.

Pirner: Well, it’s tiresome, period. Anyone can tell you that touring takes it out of you. There’s no reckoning with travel; it becomes more agonizing when you have to be on your toes for hours, because it really doesn’t fit in with your travel schedule. That type of thing is merciless and endless, and I’m in, you know? I’m on that ride, so if we come across a problem on the road, and we solve that problem as a band, within our own organization, we are heroic!

That’s pretty much how it is. We do what we’ve always done. It’s never been easy, and it doesn’t get any easier when gas prices go up or whatever. It definitely becomes more abstract, and it doesn’t get any easier as we get older, either. You’ll get up, and you’ll say to yourself, “I don’t want to eat this stuff today,” or whatever. That part is pretty obvious, but it is my element, and I do look at people like Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson who never left the road, and I’ll think, “Man, if I can get to that from here, I’m gonna be OK.”

I totally understand why Bob Dylan doesn’t come off the road, and that is cataclysmic, kind of fucked up. To me, those three guys are perfect examples of guys who don’t know it any other way. Willie would rather be on his bus than be anywhere else, except when he’s on stage, and I can relate to that. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing, but you know … It’s my life, and I like going out there and seeing how it’s going in Montana, or wherever the hell we happen to be playing on any given day.

MIM: When you’re out on tour and not busy with performing or doing meet-and-greets and interviews, what are some of the things you do with your down time to relax or entertain yourself?

Pirner: There’s not a lot of time to do that shit on the road. God knows, there are a lot of people who have tried. Many people try to bring a porta-studio, or they’ll try to have some other activity going on, but most people are lucky if they can get their workout schedule going, if they have something like that which they need to do every day. I’ve watched guys try to do it, and again, it’s pretty heroic to be that dedicated to jogging every day and do it on the road, and it impresses me. But I can’t do it.

My bass player looked at me the other day, and he said, “You’re kind of always getting ready for the next show,” and I said, “Yeah, I guess I am.” You hang up the wet clothes, you wait for them to dry, and you try to get some food and some sleep, and then you play again. That’s what makes the most sense to me on the road.

MIM: What kinds of things influence your musical tastes these days? Have your tastes in that regard changed much over the years? What do you enjoy listening to?

Pirner: In my CD player right now I have the new Queens of the Stone Age CD, and I took out “All Blues” by Miles Davis and slipped it in there. I was just looking for a record as a gift, and I noticed Kanye West’s packaging is really great, and so is Jay Z’s. They’re both embracing the sort of Andy Warhol packaging.

It’s just weird because of how strange the industry is … I just bought Jay Z’s “Fade to Black” concert at Madison Square Garden, and it is great. I love watching it; it sounds good, and you’ve got Questlove playing the drums, and the whole feel — a lot of guest stars and the crowd singing along to all his raps, it’s really cool to watch. And when the new ad campaign came out, it started popping out at me when I wasn’t ready for it.

Then I got into a band called Cage the Elephant. I like listening to all kinds of stuff. There’s always some incredible music here, and I’m never far away from a gratifying musical experience while I am in New Orleans. I really like hip-hop, so I listen to a lot of that stuff. I really like Pharrell, and I bought his last record, and I can’t stand it; I think it’s horribly cynical.

So, you know I check it all out, and in the meantime, I’m just making music and listening to the girls that came over and sang yesterday that just blew my mind. Three sisters who sing harmonies just happened to be in my studio, and I was like, I can’t believe that this is happening! They were awesome! The girls are singing background vocals on a record I’m producing by a guy manes Jamie Bernstein. They’re the Nixon sisters singing background vocals, and they just blew us all away.

MIM: Besides touring to support the upcoming releases from Soul Asylum, what is ahead for you and the band in the future?

Pirner: We’re pretty concentrated right now. I’m trying to finish up this record that I’m producing before I leave town to work on Soul Asylum material, and between those two things, I’m playing gigs, and that’s pretty much the perfect situation for me. So I’m working a lot, I’m happy to be working, and hopefully that is the way it will be, more often than not.

When it’s not happening like this, I get really nervous, and I’m not very comfortable. I worry that the jobs aren’t coming through. This record is turning out really good, I’m excited about it, and we’re trying to get it finished, because everybody’s summer plans are starting to kick in. Every summer, I play different gigs than the rest of the year, because it’s time for the outdoor shows. So that just switches up the ebb and flow of things, and now that you’ve got me talking about it, I’m realizing that it hasn’t always been the case. If things continue on the way they are going for the next two months, forever, I’ll be just fine. That’s not going to happen, but we’ll see.

The point is, I guess you just never know. The music business is terribly insecure, and unless you’ve figured out how to make a steady paycheck out of it, you’re probably in the majority. Even bands that seem relatively successful have this creeping feeling of “how long will this last?” It’s just different enough that the fear factor is supposed to be worth it.

I’m not a session player who takes calls, goes, and does gigs. There are a lot of great players in New Orleans who can work a five- or six-day week, and play six different gigs every week, and that makes me horribly envious that they never have to leave town. It’s great, because they’re in the house band in six different clubs, six days a week, and have a steady, life-long gig. Those people would say, “Dave you’re full of shit!”

It’s a real “grass is greener” situation, but I can’t imagine how it couldn’t be. The hope is for more, better things to happen so the band can keep doing what it’s doing. I just want to keep the guys in the band happy. They need the same things I need to do — to be playing music and supporting their families, and making enough money to make their nut, and it’s different for everybody. But we’re all in it together, and our fate is in our hands. Every time we play a good show, we hope that it opens the path to the next gig. As basic as that is, that’s pretty much life as we know it.

You can find Soul Asylum on the Internet at www.soulasylum.com for tour dates, band info, and downloads of their latest music.